The Miasmic Theft of Modernity:

Sulfuric Aromata and Early Modern Empires

Andrew Kettler

“Altered conceptualizations of good and bad airs floated into the atmospheres of modernity originally included categorizations with little basis in replicable inductive reasoning. Rather, the delineation of good airs and bad airs into the Enlightenment frequently involved seminal roots within fictional tales of morality and religion.”

Volume Two, Issue Two, “Senses,” Essay

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, Image 369 [371] of El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, 1615. Det Kongelige Bibliotek. Source.

Image 369 [371] of Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (1615) depicts an encounter between a member of the Andean Inka community and a representative of the Spanish colonial effort. “Cay coritacho micunqui?” the Andean asks. “Is this the gold you eat,” referring to Iberian greed and persistent efforts to extract precious metals from indigenous land. Though the Spaniards did not, in fact, eat gold, the implicit ubiquitousness of colonial extractivism presents a crucial factor in understanding how these different groups perceived one another in initial moments of contact—and particularly, one might argue, through the senses. As Andrew Kettler argues, for Spanish colonists these perceptions often involved a sensorial process of demonization and dehumanization that justified imperial abuse as well as capitalism. Atmospheric miasmas of sulfur in the New World, West Africa, and East Asia consequently signaled hell to many travelers struggling through new encounters on troubled seas and within strange lands. And as the metropoles of London, Madrid, Lisbon, and Paris increasingly denoted sulfuric aroma to ideas of profit, hygiene, fumigation, gunpowder, and industry, the colonized periphery was purported to emit the devil’s sensory significations. Observing how instances of European capitalist violence merge with religious perceptions of evil and sulfuric atmospheres in the so-called New World, Kettler offers that a synesthetic sensorium is crucial to understanding how capitalism was tested through colonial practices to become prophetically axiomatic, building discursive otherings that rationalize the continued existence of increasingly abusive systems.

- The Editors

The insurrectionist Martin Luther, informed as many other Europeans were to the feared atmospherics of a vengeful God, offered in A Sermon on Keeping Children in School (1530), that he would not be surprised if his fractured land of Catholic indulgences and Priestly hierarchies would soon face punishments akin to what rained upon Sodom and Gomorrah. For Luther, the German people committing “ten times” as many sins as the citizens of those ancient sites would soon face atmospheric wrath if moral education regimes did not shift in the direction of early Church paradigms.1 The foundational figure in the Reformation proposed new pedagogical tenets to hopefully preempt this punishment through proposing that it “would not be surprising if God were to open the doors and windows of hell and pelt and shower us with nothing but devils, or let brimstone and hell-fire rain down from heaven and inundate us one and all in the abyss of hell, like Sodom and Gomorrah.”2

Luther’s nightmarish visions introduce the idea that during the sixteenth century atmospheric and geologic violence existed in the territories of the Gods; rumbling, erupting, blowing, and showering the sinful with anger. Before the Early Modern Era, only beings with supernatural force could command changes to the interior fires below the crust or the moving clouds above the Earth. With colonialism on the periphery and in the productive factories of the metropoles in the centuries to follow, a new deity emerged at the primitive gates to the Anthropocene; a totalizing force able to maneuver geological and atmospheric conditions at will, in shorter and shorter time spans, blackening out the sun in cities and tearing apart the crust of the earth with high-powered chemical waters.3

The transition from a sixteenth century dogma including atmospheric influence from the Gods involved a restructuring of what beings could commit worldly violence. A new and nearly comprehensive “God” emerged within the airs of the Early Modern Era, set to perform more atmospheric violence that any previous spirit in the historical canon. This prosthetic spirituality stimulated by the capitalist fetish was reborn in the same space above, committing violence from the skies, imposing the same anxiety and fear of existential and precarious terror as before, especially upon colonized, proletarian, black, and brown bodies bearing the brunt of ecological crisis.4

Altered conceptualizations of good and bad airs floated into the atmospheres of modernity originally included categorizations with little basis in replicable inductive reasoning. Rather, the delineation of good airs and bad airs into the Enlightenment frequently involved seminal roots within fictional tales of morality and religion. Modern “atmospherics” are defined in conjunction within latent aspects of these applied religious semiotics and the noises, smells, diseases, fumigations, and bombs of contemporary corporatized colonialism informed by processes of hyperstition and reification that remain essential for the means of production to continue violating the earth.5

Capital specifically generates universalizing normativities to produce a superstructural mundialization upon the transnational proletariat. To expose the international power of capital to create a justifying early modern discourse of primitive accumulation through religious inspiration, this essay consequently follows common themes of European semiosis to analyze a structural semantics common across diverse forms of imperialism in the Atlantic World. Across these connections of core and periphery, through encounters and exchanges, religious fictions functioned as seminal parts of a protentional force of hyperstition within narratives that discursively rationalized the rise of capital.6

Part of superstructural discourse consistently works to manifest beliefs about good and bad atmospheres, at different times expressing public sphere beliefs that the sulfuric airs of the Industrial Revolution cleansed the nineteenth century skies, even as children developed rickets from a blocked-out sun and toxified blood from polluted waters.7 The capitalized processes of discursive reification about the environment also manifested beliefs about good and bad airs racially, indicating that a stereotyped body smell of Africana and other “black” colonized populations signified what subalterns could better take the violence of modern labor due to supposedly thicker and smellier skins.8 In gendered fields of the corporeal atmospheric, many a burned or drowned witch also faced the violent embodiments of Manichean categories that included brimstone airs within semiotically influenced domestic spheres.9

The introduction of discursively magical Christian binaries into the atmospheres of the colonial periphery began with a corporeal language and embodied semiotics of the stinking depths of hell. Over the Early Modern Era, the devil and his toadies left Europe for the periphery, cleansing the metropole through discourse about evil in the world being elsewhere. These discursive colonial processes involved fictions becoming reality and helped implement capitalism at the colonial root, under the vegetation pushing upward through the geologic, through the manufacture and violations of modern weaponry, and above within the humid airs atop the growing Plantationocene (Figure 1).10

Figure 1: Sulfur and sulfuric compounds are directly included in many current industrial and agricultural processes, including steel pickling, rubber vulcanization, and diverse formulas for insecticides and fumigation. The yellow element and its compounds also exist as part of many different byproducts from industrial processes, especially from fossil fuel burning. “Sulfur Dusting of Grape Vines, 5/1972.” National Archives. Record Group 412: Records of the Environmental Protection Agency, 1944 – 2006. DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972–1977.

Fanon in the Heavens

Structurally, reifying categorizations of good airs and bad airs remained important for colonial projects well into the twentieth century. Within Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial masterpiece, The Wretched of the Earth (1961), colonized spaces of the last century were teeming with “atmospheres of violence.” In Fanon’s psychiatric analysis, this violence existed within colonial spaces as a particular mediation between the colonizers and the colonized, and, as foundational within the earlier Black Skin, White Masks (1952), as partly inside the violated psyche of the colonized self/other. The specific psychic conflict in the mind and body of the colonized, imposed by “moral” education regimes, created a structure of “inhibition” through the development of a precarious “atmosphere of submission.”11

The Wretched of the Earth is filled with many references to the “atmosphere” of these structurally analyzed colonized spaces: in the public spheres of the colonial intellectuals, as central to magical local spiritualisms, and in the crucial apparatuses of bureaucratic control. For Fanon, the French West Indian Postcolonial leader in favor of the Algerian War for Independence and many other violent anti-colonial movements of the 1950s, it was also within the colonial atmosphere that resistance took root in the emotions of the local youth “growing up in an atmosphere of shot and fire” and who, following the introduction of violence by the colonized, “discovers reality and transforms it into the pattern of his customs, into the practice of violence and into his plan for freedom.”12

The roots of modern atmospherics stitch together the legacies of colonialism, settler discourse on the skies, and geologic violence that continued to overburden laboring bodies. For Fanon, atmospherics in colonized spaces articulated a sense of constant precarity upon the colonized, an always existing sense of crisis, “doomsday,” and “veritable Apocalypse” that made living outside of the present moment of survival and into the broadminded future of formative resistance nearly impossible.13 When the act of nationalist postcolonial revolt did arrive, the colonized applied a manipulation of the imperialist language of atmospherics through creating a postcolonial “atmosphere of solemnity to cleanse and purify the face of the nation.”14

Fanon explored how racialized atmospherics were applied by Westerners throughout the Global South in their desire to cyclically reinforce racial codification through environmental positioning of the oppressed into threatening spaces of atmospheric violence, especially concerning the increased use of the toxic insecticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) as a metaphor to the abusive soundscapes of moral evangelizing. When discussing the broader myths that upheld colonial depravity, Fanon discussed how the anti-mosquito nerve-poison “destroys parasites, carriers of disease, on the same level as Christianity, which roots out heresy, natural impulses, and evil.”15

The application of public health discourse concerning mosquitos, malaria, and DDT upon the colonized that Fanon defended represented a patterning of categories concerning atmospheric power akin to the bells, confessions, and incensed airs of colonial Christian education. Fanon understood that the colonized in these precarious spaces of carcinogenic toxins and colonialist control through mythic othering also faced psychosomatic disorders of stasis necessitating “combat breathing” and other survival modalities imposed by the colonizers’ falsely reified epistemologies of what is good and what is evil. The inability to breathe, so potent in modern discussions of race, surveillance, and policing in the West, was formative for Fanon’s understanding of the colonial production of precarity upon the subaltern; an embodied manifestation of the static as a different temporality ahistorical to the normative Western progressive timeline.16

Fanon was not the only post-colonial figure to discuss the violence of these “civilizing” colonial projects as founded in religious discourse of evangelical moralizing tied to capitalism. Morality was also militarized in the atmospheres of the colonial worlds described within Eduardo Mondlane’s Struggle for Mozambique (1969), which articulated the roots of colonialism in the religious rhetoric of submission within the enduring Portuguese Empire in control of the nation until 1975.17 Mondlane framed these colonial projects through summarizing that military pacification involved a discourse that worked to alter the meanings of good and evil within colonized spaces. The Portuguese specifically worked to “paint their activities in favorable moral terms for the consumption of public opinion.” Asserting Africans had “no morality and no education,” the colonial powers contended intrusion was a common good for the production of “moral unity.”18

What Mondlane called “spiritual pacification” from the Catholic Church, supported by the frequently mentioned air power of the Portuguese military, rings analogous to the soundings of “atmospheric” violence Fanon offered as emerging from the cleanliness campaigns of DDT and the associated settler evangelizing from white European proselytizers. Satirically employing the very demons that the Portuguese stated needed to be ridded out of Makonde regions of Mozambique, some African artists in the areas discussed by Mondlane used inquisitive imagery of a Madonna holding a demon instead of the child Jesus and priests regularly portrayed with animal feet, as tied to traditions of the hoofed devil persistent throughout the Western canon.19

As David Chidester has summarized, “These interreligious engagements in colonial situations reshaped subjectivities of both colonizers and colonized. Colonialism, therefore, was not only a military, administrative, and economic project; it was also a cultural intervention that produced unexpected consequences in forming new senses of self and other in a changing interreligious environment.”20 Postcolonial and postmodern scholars of atmospherics often continue questioning how subaltern populations in the colonies or ghettoized spaces in the Global North are racialized and gendered through atmospheric language that is then used to trap those populations into dangerously polluted atmospheres, often through discourse on disease and quarantine, as within recent histories of Jewish populations in New York City and Asian Americans in San Francisco.21

Atmospheric historiography is vast, ranging from the temporalities of Henri Bergson, the readings of aura from Walter Benjamin, into the umwelt of Jakob von Uexküll, through the studies of atmospheres in the spatial works of Otto Bollnow, the bodily feelings and concepts of reception described by Hermann Schmitz, the discourses of taste and the “oral sense” in the analyses of Hubertus Tellenbach, and into the social phenomenology of Alfred Schutz. Recent readings of sensory atmospherics include focused dialogues on aesthetics, staging, and architecture within analyses from Gernot Böhme, emotionality in the spatial research of Tonino Griffero, and on new media atmospheres from Christiane Heibach.22

Syntheses of these more theoretical academic works are frequently pulled together in the recent field of embodied philosophy focusing on “resonance.”23 Much informed by readings of Foucauldian and Bordieuan biopolitical theory and how society educates feelings of space through discourse, modern readings of atmospherics also often turn to questions of military violence, biological semiotics, and governmentality, as within respective studies from Peter Sloterdijk, Thomas Sebeok, and Jürgen Hasse.24

Postmodern particulars of race, class, and gender emerged within atmospheric studies in the past few years to a significant force for the field that often is still overburdened by phenomenological universals that date back to communication theory from Jakob Böhme and the noumena of Immanuel Kant, both essential to the parturition of German Idealism. Particularity specifically leads within the recent feminist eco-criticism of Stephanie Clare and the readings of race, “settler atmospherics,” and “microclimates” in Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016).25 More to the focused questions of sensation, atmospheres, and racism, Connie Chiang’s introductory work on odors, fishing industries, drying squids, and Chinese laborers in California specifically instigated a more concentrated modern discussion of airs, smells, and xenophobia.26

In A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (2018), Kathryn Youseff positioned atmospheric and geological knowledge of the Anthropocene as essential for gaining appreciation of the toil of racialized workers throughout the globe.27 In The Smell of Risk: Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics (2020) Hsuan Hsu has centered analysis that exposes Environmental Racism in diverse toxic spaces, as within communities positioned near freeways and proximate to runoff of agricultural pesticides. 28 Numerous other scholars, including researchers on colonial hygiene projects, miasma theory, urbanization, sick building syndrome, and Environmental Justice, have also included discussion of the semiotics of experience of atmospheres involving false justifications for environmental oppression.29

Colonial atmospherics that categorized the space around and above indigenous populations as demonic accelerated oppressive semiotics of the Early Modern Era into the modern world discussed by many of these authors of sensory atmospherics. Literatures of the contact zone in the early Atlantic World, including images and aesthetics that frequently marked indigenous lands as beneath an often-hovering devil positioned in the atmospheric plane, worked to set up a common understanding that certain aspects of colonial violence and ecological imperialism were needed to control specific laboring populations in order to create the supposed great leap forward that capitalism maintains at the base of superstructural discursive frameworks.30

In the battle between different forms of semiotic magic at the core of modernity, which set the enchanted semantics and military rationalization of Capitalism, Christianity, the State, and Mammon’s fetishized aesthetics against the enraptured spaces of diverse indigenous worldings, atmospherics were central to a dialogic conflict over the very ability to access the reality of “what is” at the basis of ontology. These issues of ecological perceptions are currently essential to understanding the reification implicit for modern questions of environmentalism and how to create green consciousness to counter polluter and profiteer fictions that frequently become truth in the greenwashed public sphere (Figure 2).31

Figure 2: Sulfur is also included in many modern military applications, linking a longer tradition that included sulfur as one of the three main ingredients in original black gunpowder with the modern warfare of atmospheric violence from bombs and toxic smokes. “This weird figure is a chemical warfare man carrying two Sulphur Trioxide smoke bombs.” (U.S. Air Force Number 23490AC). National Archives. Record Group 342: Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, 1900-2003. Black and White and Color Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel-World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940-ca. 1980.

Satanic Atmospheres and the Power of God

European colonialists of the sixteenth century often believed that atmospherically sulfuric odors signified evil in the world.32 This categorization of sulfur and brimstone atmospheres was a sensory practice educated upon the Western mind through a religious habitus that cultured the senses to perceive sulfur as evil. Areas of the world that were believed to be infected with the ancient evils of the devil were specifically deemed to produce malevolent pestilence. This tradition of understanding evil in the world through atmospheres involved placing malevolent smells upon geographical spaces as potential markings portending the coming of a providential force of curative sanitation and the invasive white bodies promoting settler morality as a therapeutic for supposed indigenous indolence.33 As Michael Taussig has described most clearly in the later discursive contexts of Mimesis and Alterity (1992), the colonist structurally gained “healing power,” or the magical power of the means of production, through a competing dialogue that painted the indigenous as “devil,” which led to a constantly changing and contested discourse of “interlocking dream-images” and the associated “reproduction of social life” in colonized spaces built upon the binary of civilization and savagery.34

As in Lambert Daneau’s Dialogue of Witches (1575), devout Europeans of the sixteenth century often concluded that othered regions of the world sensed of the devil. In the English translation of Daneau’s work, the reformed writer specifically endorsed that Persia and Italy were so poisoned by the evil of heretical religions and Catholicism that the “pestilent smell or vapour doth…infect an whole region through which it breatheth…and infectious diseases are thereby engendred.”35 As within English Bishop Thomas Watson’s later Beatitudes (1671), other spaces of the world that were deemed to be cursed with ancient evil smelled specifically of sulfuric malevolence. Therein, the region of modern Israel near the Dead Sea that may have been Sodom, “that was once the wonder of Gods patience, is now a standing Monument of Gods severity; all the plants and fruits are destroyed; and…that place still smells of fire and brimstone.”36 Sulfuric atmospheres in numerous works informed the perceptions of many travelers who left European shores to disembark on the colonial world, enlightening diverse cultural and sensory clashes throughout Africa, Asia, and the New World that were often defined through medical and moral fictions that frequently described colonial invasions as moral battlegrounds in the encounter between a cleansing God and the persuasive devil, as plainly signified through the floating devil prominently featured in Conquistador Pedro de Cieza de León’s La chronica de Peru (1554) (Figure 3).37

Figure 3: Pedro de Cieza de León’s La chronica de Peru (1554) highlights sixteenth century imaginings of an atmospherically dominant devil floating above indigenous and Spanish populations in the New World. Here, a figure is being controlled into extreme violence including the removal of the beating heart from a living body. Nearby, bodies hang in further preparation for rituals awaiting instructions from a winged beast preaching from an altar. Pedro Cieza de León, [La chronica de Peru. Part 1] Chronica del Peru ...(An Anvers [Antwerp]: En casa de Martin Nucio, 1554), illustration; verso leaf 40. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

In diverse heretical spaces of the world, sulfur and brimstone connotations of the atmosphere were commonly printed within Western European travelogues. In their writings about the coastlines of Africa, both English traveler Thomas Herbert and metropolitan scholar Ralph Bohun contended that sulfur emanated from deep within the Dark Continent. Herbert’s Relation of Some Yeares Travaile (1626) provided evidence of the idolatrous nature of Africans on the coast near his passage of the Cape Verde Islands through the “sulpherous and raging hot” air that caused “sweating all day and night.”38 Bohun’s Discourse Concerning the Origine and Properties of Wind (1671) similarly provided that the West African coast included atmospheres of “putrid and sulpherous exhalations” that often caused diseases and fevers among African population and for many European travelers to the region.39

This stench of sulfur in Africa, and frequently within the New World, often signified hellish atmospheres to devout travelers struggling through new encounters on troubled seas and within strange lands. While traveling in the Caribbean during the late seventeenth century, Welsh explorer Lionel Wafer relied on his nose to detect these dreaded malevolent aspects of the otherworldly atmospheric. During his voyages, a strong storm caused the air to bring forth a confusing “sulpherous smell,” a common atmosphere detected by many on these tortuous Atlantic voyages. The retinue camping near shore upon the Darien Peninsula sensed the storm through a spiritual worldview that connected heaven with the intense falling rains and blistering winds while offering that the air became so thick and humid that it “stifled,” or suffocated, even those in the “open air” of the coast.40 European travels in the transnational spaces of the Caribbean also involved the consistent attribution of hellish signifiers of religious sin to pirates and privateers, as with the demonic attributions commonly placed upon English privateer Francis Drake, frequently called El Dragón by the Spanish.41

Fearful perceptions on these anxious seas helped to preserve a sensory dogma for detecting the preternatural. Stuart Schwartz has described how early modern hurricanes were initially categorized by the Spanish in the Caribbean and Central America through similarly religious categories of moral or terrible airs.42 The writings of Fernández de Oviedo in Sumario de la natural historia de Las Indias (1526) include many of these observations of early Spanish travelers in the region. In Oviedo’s contention, the devil was believed to be “a former astrologer” who could alter the skies and airs when Spaniards and Native Americans were actively not following the Lord’s commandments. Natives, especially the Caribs throughout the littoral, were often confirmed as devilish to the Spanish in these regions due to their ability to predict the coming of powerful and socially altering hurricanes.43

Oviedo’s discussion of storms included defining the obscure term tequina as a spiritual practitioner among the Cueva of Mesoamerica as a figure who consistently convened with the devil. For the Spanish colonists, the tequina manipulated the Cueva to worship the devil due to their “poor and unprepared…defenses against such a great adversary, to whom they give the name tuira.” The tequina appeared to inspire demonic worship to the Spaniards because he was believed by the Cueva to retain “control over the weather.” The practitioners “often see things happen which were foretold a few days earlier,” and consequently are supplied “credit for everything else,” and are sacrificed to “in many different ways: in some places with blood and human life, in others with aromatic…and also evil-smelling incense.”44 These Spanish contentions about indigenous ritualism, which linked meteorological atmospheres with perceptions of miasmic malevolence, assisted in the broader project of colonialism through a continuing process of religious othering interrelated to labor acquisition.45

Peter Martyr, the early modern Dutch chronicler of Spanish history, also offered a dialogue on hurricanes in the early sixteenth century, providing that the indigenous fear of hurricanes was occasionally transposed in troubling moments of colonization. Rather than the intensive terror of hurricanes from above caused by what the Spanish supposed was the devil, indigenous nations began to fear a new power of “lightning” that was recently arriving from the firmaments. During Vasco Núñez de Balboa’s invasion of Chiapas in the 1520s, the approaching Native American leader, “fully armed and accompanied by a multitude of his people, advanced menacingly, determined not only to block their way but to prevent them crossing his frontier.” The quickly released Spanish cannonade “reverberated amongst the mountains, and the smoke from the powder seemed to dart forth flames; and when the Indians smelt the sulphur which the wind blew towards them, they fled in a panic, throwing themselves on the ground in terror, convinced that lightning had struck them.” Taking advantage of this transposition of gods from above, storms, and military power, the colonizers swiftly took advantage: “While lying on the ground or wildly scattering, the Spaniards approached them with closed ranks and in good order. In the pursuit they killed some and took the greater number prisoners.”46 In these moments of fear in the contact zone, including the infamous slaughter of supposed indigenous sodomites by the muscular dogs of Balboa’s retinue in 1513, the colonized Caribbean materialized a new spiritually inspired ecology upon the colonized, partly through manipulating discourses about a meteorological battlefield of good airs and bad airs and the demons that floated within those skies while inspiring malevolent, homosexual, and slothful lifeways.47

Europeans continued to face some of these fears as well, envisioning a devil in the New World that could emerge into their camps and conquests. William Dampier’s A New Voyage Round the World (1699) depicted an implicitly hellish scene of tornadoes and lightning storms, including an “Air smelling very much of Sulphur,” encountered by Captain John Eaton in his 1684 travels to Peru.48 In tangential geologic contexts, while travelling south of the Rio Grande during the middle of the seventeenth century, English author Thomas Gage noted that specific earthen-ware cookery often was deemed superior to other pottery because it was created in areas that the Spanish deemed to be near to the “mouth of hell,” which included a nearby volcano that breathed “a thick black smoak smelling of Brimstone, with some flashes now and then of fire.” The Spanish, to Gage, believed this emission to be from the depths of perdition due to the miasmas of brimstone emanating from inside the geologic formations.49

Throughout the Early Modern Era, atmospheric and geologic powers shifted away from an Abrahamic God who could punish all populations for their sinfulness into colonized spaces that were classified as inherently underneath devilish atmospheres. Through moving much of the atmospheric powers of God from their homelands through the processes of empire, discourse manipulation, and disenchantment, Western Europeans preconditioned the semiotics of the coming Anthropocene, whereby humans later emerged as the utmost arbiters of atmospheric violence the world over, discursively tested upon the colonized and then made into the forever filling atmospheres of the universalizing Capitalocene (Figure 4).50

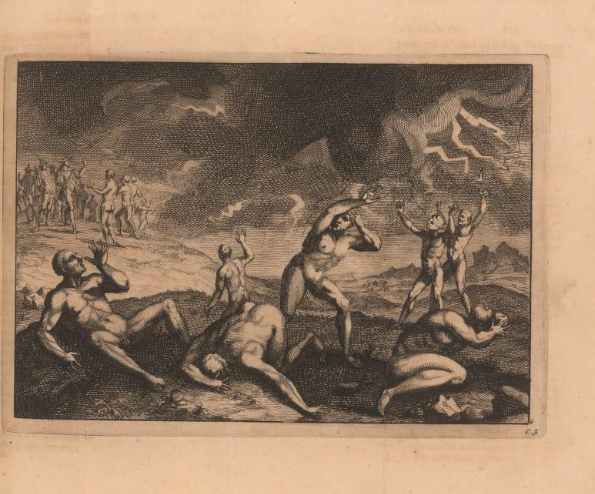

Figure 4: Many early modern Europeans learned of the demonic atmospheres supposedly surrounding Native Americans from their interpretation of the Tupi, a Brazilian nation brought to much of the European public sphere through the images in Theodor de Bry’s America, within multiple editions starting from 1590. Above is a later rendering of an illustration from De Bry that portrays the evil spirits of New World atmospheres tormenting the Tupi with the storms, soundscapes, and lightning of a hurricane. Pieter Vander Aa, Naaukeurige versameling der gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indiën ... zedert het jaar 1524 tot 1526 (In het ligt gegeven te Leyden [Leiden]: Door Pieter Vander Aa, boekverkoper in de St. Pieters Koor-steeg, in Plato, 1707), fold-out plate; vol. 15, [part 2], following p. 128. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Atlantic Immersions and Subaltern Demons

Alongside the relations of colonial development, Catholic providence, and “willing” Native American traders commonly found within Cristóbal Colón’s “Carta a Luis de Santángel” from 1493, prints of Native Americans beneath a many-headed demon included in Pieter van der Aa’s edition of Girolamo Benzoni’s Historia del mondo nuovo (1519) created an early entrenchment concerning ideas of religious inspiration on the land through the placing of indigenous bodies in subservient, languid, and needful positions (Figure 5).51 Although many of these devout terminologies and aesthetics arose from Catholic superstitions and burst into the colonial world with the pace of hubris after the Reconquista, the religious languages of the Atlantic World were nearly always transnational in their construction. As Jorge Canizares-Esguerra has aptly stated regarding these interactions: “Despite all their differences, intellectuals in both the British and Iberian Atlantics saw Satan as enjoying control over the weather, plants, animals, and landscapes in the New World….demonological views of nature and colonization encouraged a particular perception of the American landscape among Europeans: the New World often came to be seen as a false paradise that to be saved needed to be destroyed by Christian heroes.”52

Figure 5: The engraving here, including three prominent demonic images and many smaller flying demons is derived from illustrations in Theodor de Bry’s America, and was included in Pieter van der Aa’s 1704 published translation of Girolamo Benzoni’s Historia del mondo nuovo (1519). That original work from Benzoni, a merchant traveler from Milan, was vital in the later creation of a Black Legend of Spanish maliciousness that the English later used to justify their own colonial violence in the Western Hemisphere. Girolamo Benzoni, De gedenkwaardige West-Indise voyagien, gedaan door Christoffel Columbus, Americus Vesputius, en Lodewijck Hennepin. Behelzende een naaukeurige en waarachtige beschrijving der eerste en laatste Americaanse ontdekkingen, door de voornoemde reizigers gedaen, met alle de byzonders voorvallen, hen overgekomen. Mitsgaders een getrouw en aenmerkelijk verhaal van de opperhoofden der Spanjaarden onderlinge oneenigheden doenmaals in America, trans. Pieter Vander Aa (Te Leyden: Pieter Vander Aa, 1704), fold- out plate; part 1, following p. 64. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Consistently repeated imagery of these demons above worshiping and wanton Native Americans alleged an atmosphere of evil secured through offerings provided to the pitchfork wielding, horned, and obscurely headed beasts in command. As in the imagery associated to Theodor de Bry’s America prints from the 1590s, which borrowed from the writings on cannibalism of Brazilian traveler Hans Staden in Warhaftige Historia (1557), Christian settlers believed themselves to be entering a world where horned demons assaulted and punished the Tupi of Brazil with rocks, and flighted demons spread their wings above atmospheres ripe with smell of cooking flesh (Figure 6).53 Conquest was believed justified through this rhetoric, whereby the entrance of any colonial endeavor, no matter how violent, could be justified in the name of freeing lands and New World atmospheres from demonic manacles. Christian protagonists reified false fictions of religious atmospherics, creating a colonial reality of impure airs and the bodies that produced them to justify colonialist’s ideologies that spaces had to be cured via Eurocentric concepts of purity, labor, and extraction from the land.54

Figure 6: Theodor de Bry’s America was a common touchstone for those in Europe of the seventeenth century researching Native America. This illustration from part three of De Bry’s America of 1592 specifically highlights interpretations of the Tupi from inspiration most likely arriving from Hans Staden and Jean de Lery, travelers to Brazil in the sixteenth century who faced the threat of cannibalism while misunderstanding the meanings of that violence. The imagery here portrays the indigenous nation beset by demons from above, beating Tupi with rocks, flying over their homes, and instigating demonic coitus. Theodor de Bry, [America. Pt 3. Latin] Americae tertia pars memorabile[m] provinciae Brasiliae historiam contine[n]s ...(Frankfurt am Main]: Theodori de Bry, 1592), illustration, p. 223. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Many of these broadly European sensory ideals were created in cyclical exchange betwixt the Catholic rhetoric of Iberian conquests in the New World and the reformed poetics of the English public sphere. For an example of these myriad Iberian beliefs, Jesuit missionary Andrés Pérez De Ribas attributed the devil as a cause of the Tepehuán Revolt of 1616-1620 against Spanish rule in territory that is now modern Mexico. That failed revolt, which aimed to oust Catholic and Spanish colonial dominance in Tepehuán territories, involved discursive constructs of good and evil concerning what regional power retained spiritual rights to the worldly holdings. For example, De Ribas wrote in History of the Triumphs of our Holy Faith amongst the most Barbarous and Fierce Peoples of the New World (1645) of the wandering devil who tempted specific indigenous groups to revolt against Spain and the Catholic God. This demon, who was said to often entice native groups with powerful persuasions of dominance over their neighbors and through the iconography of his image within handicraft stones, had a signifying cape “covered in rich plumage” that trailed with a “noxious odor.”55

Similar connotations arrive to the colonized archive from early Spanish discussions of the conquest over the Aztecs. Son of a royal mine official and parish priest Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that Today Live Among the Indians Native to This New Spain (1629) provided a summary of many of these atmospheric tendencies in the preternatural areas of Central America. The record of Aztec religious practices included in Alarcon’s work offered concerns that the devil was involved with specific customs that involved the burning of rags that enclosed idols to be placed within scorching black pots to, in the Spanish perceptions, release demonic atmospheres into the skies of the region through conjuring the “Air-spirit, the Green Demon.”56

Bernal Diaz del Castillo’s Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (1632), published more than a century after Diaz’s service for Conquistadors in Mesoamerica of the early sixteenth century, also included references to hellish atmospheres. The leading priests in Aztec society responsible for human sacrifice, according to Diaz, “wore black cloaks like those of canons, and others smaller hoods like Dominicans. They wore their hair very long, down to their waists, and some even down to their feet; and it was so clotted and matted with blood that it could not be pulled apart. Their ears were cut to pieces as a sacrifice, and they smelt of sulphur. But they also smelt of something worse: of decaying flesh.”57 Often informing English traditions, and in turn being educated by English texts, these demonic connotations from the Iberians, including the Spanish assertions of the demonic sodomy of these Aztec practitioners, involved the frequent marking of indigenous rituals of the Western Hemisphere as satanic through the atmospherics of perdition and the signifying sensory aspects of sulfur and brimstone.58

Fernando Cervantes’ reading of the inquisition records of Fray Pablo Sarmiento in New Spain, who was stationed near the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro, also described these sensory trends when summarizing the “most intolerable stench” of evil that was emanating from a possessed woman who was being tormented by many demons in the late summer of 1691. To exorcise these demons, Sarmiento provided the woman “two or three holy drinks” that forced her to expurgate three large avocado stones, signifying the cleansing of evil odor from the room. Once the stones were removed from her throat, a stinking toad was discovered living beneath the former blockage. This demon was thereafter burned with holy fires. As the toad died, the amphibian emitted an “indescribably unpleasant smell” into the surrounding environment. Although the toad was removed, the atmospheric violence on the woman, Juana de los Reyes, did not abate. As the ordeal continued, the exorcists were overburdened with her signifying evil odors and Juana was continuously choked by demons who invaded her lungs with what was established to be black wool cloth.59

Early modern English voyages to the East likewise involved sulfuric sensations as possibly emanating from hell. Englishman Robert Knox, a Captain traveling to the East Indian island of Ceylon during the sixteenth century, summarized an encounter with inhabitants who believed a tree that “no sort of Cattle will eat,” because it smelled of sulfur, was a sign of the presence of Satan.60 A similar allusion to the sulfuric devil and his pungent signifiers in worldly environments was presented in Thomas Herbert’s later travels beyond West Africa, which perhaps elicited references to the Garden of Eden for English readers of the seventeenth century. His travel accounts of India included an encounter in Cape Comorin that contained trees “strange both in shape and nature.” Herbert, while curiously pondering an extraordinary tree, decided to taste its nectar. After a period, his “mouth and lips” were “malignantly wronged” by the taste of sulfur and brimstone.61

Rituals developed among sailors entering these threatening sensory atmospheres of the antipodal Tropics. When mariners on English ships crossed into equatorial regions on journeys away from their cherished and supposedly cleanly homes, they immersed themselves into what they believed was a more deeply scented and invasive environment. Part of this process sometimes included violent baths in stinking oils and tars that created a new figure that could succeed in the sensuous atmospheres of the Americas with new skin healed over recently removed layers. In Barbados of the 1790s, English traveler George Pinckard wrote of such a ceremony that involved submerging the sailor passing into the tropics for the first time with “a nasty compound of grease, tar, and stinking oil,” which burned the skin to be removed by sharpened razors of the crew.62

These intense rituals prepared many European bodies for the experience of excess sensation feared to be existing within the demonic New World. The boundary maintenance of the senses was also apparent to Gage in the North America of his travels. The chronicler wrote: “Thus as wee were truely transported from Europe to America, so the World seemed truely to bee altered, our senses changed from what they were the night & day before when we heard the hideous noise of the Mariners oifing up Sailes, when wee saw the deep and monsters of it, when we tasted the stinking water, when we smelt the Tarre and Pitch.”63 Such ceremony and poetic remembrance of immersion provides that the Old World sailor entered into the New World environment through a belief in the shedding of previous sensory worlds of appropriate atmospheres in Europe into spaces that included encountering a constructed and frightening ecology including demonic inspirations.64

The devil was leaving England and broader European spaces for areas of the world where Christianity and Europeans had yet to dominate. Westerners, confident that the devil was departing their homelands, placed his atmospheric manifestations in places in the world where Europeans entered to proselytize, later creating justifications for myriad imperial abuses.65 As Craig Koslofsky has recently offered, the atmospheric dualities of good/evil and light/dark involving witches and demons was informed by broader traditions of race within a European Enlightenment that began to shift the belief in a devil in the lived world to othered spaces of the globe, “where the invisible world burst into the colonial world.”66

Atmospheric superstition at home was increasingly removed in the seventeenth century, especially in Protestant nations but also in broader spaces due to myriad Enlightenment discourses on reason, science, and worldliness. As the metropole ousted the devil throughout the Early Modern Era, spaces of the world to be conquered faced renewed fictions of evil. These religious discourses were believed to vindicate imperial abuses and ameliorate any concern with environmental violations of stolen lands through emphasis on Christian curatives, as also clearly illustrated through the imagery of a punishing heaven applied to demonic Native American lands in Alonso de Ovalle’s Historica relacion de reyno de Chile (Figure 7).67

Figure 7: Native Americans in the expanding Spanish Empire of the seventeenth century were frequently portrayed as linked to the devil, and, as with the imagery here from cartographer and Jesuit priest Alonso de Ovalle, as being punished for their blasphemies by the atmospheres of the recently arriving Catholic God, sainted warriors, and angels from overhead. Indigenous populations, for this image concerning idolatry in Chile, were portrayed as living amongst demons through the relaying imaginaries of hell and devilish connotations, including snakes, tails, hydra, and the sulfur smoke from a nearby volcano. Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relacion de reyno de Chile] Historica relacion del reyno de Chile, y delas missiones, y ministerios que exercita en el la Compañia de Iesus (En Roma [Rome]: Por Francisco Cavallo, 1646), plate; following p. 302. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

The Miasmic Theft of Modernity

For many Europeans printings, the ritualism of the New World was filled with the devil’s presence. North American contexts consistently also portray the linked narratives of colonialism, whether Spanish, English, Portuguese, or French, that concluded the atmospheres of the New World were evil, stinking, and meant for the whitewashed hands of colonial morality and curative labor. In Johann Justinus Gebauer’s publication of images derived from a French traveler in Haudenosaunee territory of the early eighteenth century, Joseph François Lafitau, devilish miasma again floats above indigenous ceremony, probably involving stereotypes of a mixture of diverse Native American nations present within eighteenth century discourse (Figure 8).68

Figure 8: This print portrays an example of a Native American ritual from the transnational French perspective, appearing in Johann Justinus Gebauer’s 1752 translation of Joseph François Lafitau’s Mœurs des sauvages ameriquains, comparées aux mœurs des premiers temps (1724). The imagery again depicts a floating and miasmic demon above indigenous ritual practices, here supposedly portraying initiation rites whereby Native American awoken by the noise of the demonic appearance observe their diabolic supervisors and the atmosphere surrounding the devilish figure. Johann Friedrich Schröter, Siegmund Jakob Baumgarten, Joseph-François Lafitau, and Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix, Algemeine Geschichte der Länder und Völker von America.: Erster [-zweiter] Theil, trans. Johann Justinus Gebauer (Halle: Bey Johann Justinus Gebauer, 1752), plate 15; vol. 1, following p. 160. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Part of knowledge gathering within the novel and confusing New World and colonial spaces of the Early Modern Era involved a preternatural lens that attributed these dark atmospheres to indigenous peoples. As Kris Lane has also added concerning the notes of Diego de Ocaña, an alms collector in Potosi, Bolivia in 1601, local performance culture in the Spanish Empire frequently involved comedies that included such a commonly known character of the devil. In the specific performances described by Ocaña, the devil character would agree to a joust by sending a letter from the “dark dungeons” and “infernal caverns” near the “Stygian lakes, burning with flames of sulfur” that stated: “The Prince of Tartary, who of sulfur/ Sustains himself in the dark cavern/ Will present himself at half past five,/ And he thanks those who shall suffer until then.”69

Sulfuric and brimstone atmospheres in the colonized world, whether observed above Native American communities, influencing wayward colonists, or considered present enough to ponder about within theatre and comedy, are but one aspect of the phenomenological shift of previously malevolent Old-World miasmas merging with colonized environments that were fictionalized into what Westerners understood through religious narratives and for the promotion of the colonial project within the mineshafts at the cradle of those developments. Such acceptance of violence through narratives of miasmic evil led to greater Western European justification for their labor acquisitions of Native Americans and other imported workers, as within the gold mines of Hispaniola that triggered greater Spanish intrusion throughout the Western Hemisphere, the silver flues of northern New Spain at the outset of globalization, or deep within the tin mines of Bolivia during the Second Industrial Revolution (Figure 9).70

Figure 9: In this edition of Bezoni’s Americae pars quinta nobilis & admiratione (1595) prints from De Bry’s America were included to highlight discussions concerning the labors completed for the Spanish Empire in the New World. Here, the violence and prominence of mining labor was portrayed on Hispaniola, as Spanish observers looked upon the labor force from relaxed and lesirusly positions. Girolamo Benzoni, Americae pars quinta nobilis & admiratione (Frankfort: De Bry, 1595), part V, fig 1. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Evil, confusing, and sulfuric perceptions often attributed to the devil, his toadies, and conjurers were leaving Europe for the wider world. Religiously inspired, inherently transnational, and semiotically linked colonialist literatures of the empires offered false justifications for the supposed purification to come from colonial growth on the peripheries, providing a hyperstitional force of superstructural reification through language of atmospherics akin to Fanonian discussions of the twentieth century. Such atmospherics as a form of suppression pair with discussions of the modern Anthropocene that involve asserting racist categories to unfairly tie suppressed populations into threatening geological and atmospheric spaces marked by the industrial sins of modernity. European populations of the Early Modern Era felt justified in their use of religiously inspired othering to combat what they understood as diseased atmospherics emanating from hellish lands, as with those spaces demonstrated in the writings of Diaz, Ruiz de Alarcón, and De Ribas, and numerous images including those that inspired the prints of Theodor de Bry, as well as Diego Valades’ legalistic designs from early Mexico meant to teach moral codes to indigenous populations (Figure 10).71

Figure 10: Included above are a series of pictographs that were meant to educate Native Americans in New Spain to avoid idolatrous speech. The types of supposed blasphemy committed on the left page, as with praying to the demonic spirits pictured at the top, would be punished through different tortures on the right. Below are human forms mashed into the pits of hell, a punishment for those who dared to continue speaking indigenous idolatry into the changing religious atmospheres of the New World. Diego Valades, Rhetorica christiana ad concionandi, et orandi usum accommodata (Perusiae: Apud Petrumiccobum Potrutium, 1579), plate; following p. 281. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Categories of race, disability, class, and gender habitually link with these types of fictional atmospheric emplacements of good and evil to articulate a false consciousness about the naturalness of suffering bodies laboring within jeopardized and toxic living spaces.72 At the outset of capitalism in the Atlantic World, atmospheric violence was specifically meant for those on the periphery, facing the new prosthetic God of Capital as engineered by Western Europeans. In the metropole, the atmospheric powers of God lessened. Operationally, this analysis offers that the superstructure mapped out the future before creating the situations through which new profits emerged. That is, semiotic potential was plotted, as an experiment of capitalized insurance, for the means of production to continue moving forward, always built on acceleration. Without the indemnity that the metropolitan public would accept what capital wanted to force upon laboring classes and the environment in the future, the dromological progression into those spaces would nary occur.73

Capitalism is hyperstitionally axiomatic in this way, building the superstructural discourse about supposed indigenous immortality essential for the existence of an abusive economic base that consequently placed demoralized bodies into the laboring pits that upheld the supposed properness of constant economic growth. Through this logic out of emerging modern markets in the Atlantic World, organized number sets of possible futures already exist before they happen.74 To prepare for the environmental degradation of the later Anthropocene, the early modern superstructure pre-checked, through religious fictions of good and evil and colonialist accusations of savagery involving concepts of sulfuric and demonic malevolence in the noisy and pungent atmospheres of the New World, that the metropolitan public would receive geohistorical violence from a new source.75

Assuring future primitive accumulation for the economic base through constructing categories of who was to be considered evil and consequently meant for hard labor supported a continuing semiotic mundialization of the appropriateness of profit. The rationalization moved from the peripheral space back into the core, on standard Atlantic passages of encounter and exchange, informing the rise of a metropolitan capitalism that had already tested how to degrade a broader proletariat through a discourse of specific populations suitability to violent labor. Into the modern world, the Abrahamic God discursively lost his sole responsibility as arbiter of atmospheric violence, as colonialist discourse shifted the ability to commit ecological degradation, geologic excess, and violence from the skies to the thieves of the Modern Age, those hybristophillic disciples of Mammon.76

❃ ❃ ❃

Andrew Kettler taught at the University of Toronto from 2017 to 2019 before serving as an Ahmanson-Getty Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles during the 2019-2020 academic year. He is currently serving as Visiting Assistant Professor of Native American and African American History at Kenyon College. His work has appeared in Senses and Society, Interface, Human Rights Review, the Journal of American Studies, the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, Patterns of Prejudice, and the Australian Feminist Law Journal. His monograph, The Smell of Slavery: Olfactory Racism and the Atlantic World (Cambridge, 2020), focuses on the development of racist semantics concerning miasma and the contrasting expansion of aromatic consciousness in the making of subaltern resistance to racialized olfactory discourses of state, religious and slave masters.

- Christopher Elwood, “A Singular Example of the Wrath of God: The Use of Sodom in Sixteenth-Century Exegesis,” The Harvard Theological Review 98, 1 (2005), 67-93.

- Martin Luther, A Sermon on Keeping Children in School (1530) in Luther’s Works Vol. 46 (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1967), 213-257, quote on 254. See also, Sonja Brentjes and Dagmar Schafer. "Visualizations of the Heavens Before 1700 as a Concern of the History of Science, Medicine and Technology," NTM Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine 28, 3 (2020), 295-304.

- For an introductory survey of cultural beliefs concerning geological and atmospheric influences on humanity see, SueEllen Campbell, Scott Denning, John Calderazzo, Charles Goodrich, and Fred Swanson, “Landscapes of Internal Fire” in The Face of the Earth: Natural Landscapes, Science, and Culture (Berkeley: California, 2011), 1-56. See also, Jack Goody, Metals, Culture and Capitalism: An Essay on the Origins of the Modern World (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge, 2012).

- For metahistorical sensory changes see, Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy; The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: Toronto, 1962); Keith Thomas, “Cleanliness and Godliness in Early Modern England” in Religion, Culture, and Society in Early Modern Britain: Essays in Honour of Patrick Collinson, eds. Patrick Collinson, Anthony Fletcher, and Peter Roberts (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge, 1994), 56-83, Constance Classen, David Howes, and Anthony Synnott, Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell (London: Routledge 1994).

- For background on embodiment, pollution, and contagion see, Mel Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham: Duke, 2014), and the role of portraying pain and toxicity within lawsuits in, Ellen Griffith Spears, Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town (Chapel Hill: North Carolina, 2014), 264-290.

- For hyperstition see, CCRU, Writings, 1997-2003 (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2017). Within less absurdist science fiction worlding as the CCRU, the term is akin to “reification” (“making into a thing”) in a cultural Marxism that retains the core questions of German Idealism to consistently ponder the possible knowability of the object. See, Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (London: Merlin Press, 1923). As well, one can look to Freud, and the idea that civilization functions through a progressive creation of humanity becoming the prosthetic God, as explored within, David Wills, Prosthesis (Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2021), 100-104.

- For industrial discourse and environmental change see, Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017); Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2013); David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth (London: Allen Lane, 2019); Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

- John Mitchell, “Causes of the Different Colours of Persons in Different Climates,” in The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (From the Year 1743 to the Year 1750) (London: Royal Society, 1756): 926–949; James Delbourgo, "The Newtonian Slave Body: Racial Enlightenment in the Atlantic World," Atlantic Studies: Literary, Cultural and Historical Perspectives 9, 2 (2012), 185-207.

- Sylvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2014); Laura Gowing, Common Bodies: Women, Touch, and Power in Seventeenth-Century England (New Haven: Yale, 2003); Holly Dugan, "Scent of a Woman: Performing the Politics of Smell in Late Medieval and Early Modern England," The Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 38, 2 (2008), 229-252; Constance Classen, “The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories,” Ethos 20, 2 (1992), 133–166.

- For terminology, see the posthumanist and environmentalist assertion of the importance of eco-critical narratives as essential for producing positive future conditions within, Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke, 2016). For image see, “Sulfur Dusting of Grape Vines, 5/1972.” National Archives. Record Group 412: Records of the Environmental Protection Agency, 1944 – 2006. DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972–1977.

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove, 1961), quote on 38; Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove, 1994 [1952]).

- Fanon, Wretched, 58-71, quote on 58.

- Fanon, Wretched, quotes on 80-81.

- Fanon, Wretched, quotes on 132, 251.

- Fanon, Wretched, quote on 7.

- Fanon, Wretched, quotes on 288-289. Elsewhere, Fanon further defined this type of constant precarity and inability to breathe in colonized spaces. Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism (New York: Grove, 1994 [1959]); Romy Opperman, “A Permanent Struggle against an Omnipresent Death: Revisiting Environmental Racism with Frantz Fanon,” Critical Philosophy of Race 7, 1 (2019), 57-80.

- David Chidester, Religion: Material Dynamics (Berkeley: California, 2018), 107-111.

- Eduardo Mondlane, The Struggle for Mozambique (London: Penguin, 1969), quotes on 23, 35, 60.

- Mondlane, Struggle for Mozambique, 103-104.

- Chidester, Religion, quote on 110.

- Alison Bashford, Quarantine: Local and Global Histories (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2016); Howard Markel, Quarantine!: East European Jewish Immigrants and the New York City Epidemics of 1892 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1999); Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown (Berkeley: California, 2021 [2001]).

- Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (London: Dover, 2001 [1912]); Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, trans. J. A. Underwood (New York: Penguin, 2008 [1935]); Jakob von Uexküll, Theoretical Biology (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1926); Hubertus Tellenbach, Geschmack und Atmosphäre. Medien menschlichen Elementarkontaktes (Salzburg: Verlag, 1968); Otto Friedrich Bollnow, Human Space (London: Hyphen, 2011 [1963]); Alfred Schutz, The Phenomenology of the Social World (Evanston: Northwestern, 1972); Gernot Böhme, Atmospheric Architectures: The Aesthetics of Felt Spaces (London: Bloomsbury, 2017); Tonino Griffero, Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces (London: Routledge, 2016).

- Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2020).

- Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air, trans. Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009); Jürgen Hasse, "Atmospheres as Expression of Medial Power," Lebenswelt: Aesthetics and Philosophy of Experience 4 (2014): 214-229; Thomas Sebeok, Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics (Toronto: Toronto, 2001).

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke, 2016); Stephanie Clare, Earthly Encounters: Sensation, Feminist Theory, and the Anthropocene (New York: SUNY, 2020)

- C.Y. Chiang, "Monterey-by-the-Smell: Odors and Social Conflict on the California Coastline,” Pacific Historical Review 73, 2 (2004), 183-214; C.Y. Chiang, "The Nose Knows: The Sense of Smell in American History," Journal of American History 95, 2 (2008): 405-416. See also, Mark Smith, How Race Is Made: Slavery, Segregation, and the Senses (Chapel Hill: North Carolina, 2006), 96–114; Jonathan Reinarz, Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell (Urbana: Illinois, 2014), 85–112.

- Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2018).

- Hsuan Hsu, The Smell of Risk: Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics (New York: NYU, 2020).

- Michelle Murphy, Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers (Durham: Duke, 2006); Ellen Stroud “Dead Bodies in Harlem: Environmental History and the Geography of Death,” in The Nature of Cities, ed. Andrew Isenberg (Rochester: Rochester, 2006), 62-76; Dolores Greenberg, "Reconstructing Race and Protest: Environmental Justice in New York City," Environmental History 5, 2 (2000): 223-250; Ivan Illich, “The Dirt of Cities, the Aura of Cities, the Smell of the Dead, Utopia in the Odorless City,” in The Cities Culture Reader, eds. Malcolm Miles, Iain Borden, and Tim Hall (London: Routledge, 2000), 355-359.

- Colonial labor systems frequently involved attempts at sensory control. Jean Comaroff, “The Empire’s Old Clothes: Fashioning the Colonial Subject,” in Cross-Cultural Consumption: Global Markets, Local Realities, ed. David Howes (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, 1996), 19-38, Andrew Rotter, "Empires of the Senses: How Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching Shaped Imperial Encounters," Diplomatic History 35, 1 (2011): 3-19; Warwick Anderson, “Excremental Colonialism: Public Health and the Poetics of Pollution," Critical Inquiry 21, 3 (1995): 640-669.

- For background on perceptual worlding and capitalism see, Michael Taussig, The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (Chapel Hill: North Carolina, 1980), 228-233. For image see, “This weird figure is a chemical warfare man carrying two Sulphur Trioxide smoke bombs.” (U.S. Air Force Number 23490AC). National Archives. Record Group 342: Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, 1900 - 2003. Black and White and Color Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel - World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 - ca.1980.

- For sulfur see, Salomon Bernard Kroonenberg and Andy Brown, Why Hell Stinks of Sulfur: Mythology and Geology of the Underworld (London: Reaktion, 2013), 5-34; Alice Turner, The History of Hell (New York: Harvest, 1993); Gerald Kutney, Sulfur: History, Technology, Applications & Industry (Toronto: ChemTec, 2013); Beat Meyer, Sulfur, Energy, and Environment (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1977). See also, Karen Holmberg, “The Sound of Sulfur and the Smell of Lightning,” in Making Senses of the Past: Toward a Sensory Archaeology, ed. Jo Day (Carbondale: Southern Illinois, 2013), 49-68; Lukas Engelmann and Christos Lynteris, Sulphuric Utopias: A History of Maritime Fumigation (London: MIT, 2020).

- For more on cleanliness, embodiment, and race, see Kathleen Brown, Foul Bodies: Cleanliness in Early America (New Haven: Yale, 2009); Alison Bashford, Imperial Hygiene: A Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2004); Alexis Shotwell, Knowing Otherwise: Race, Gender, and Implicit Understanding (University Park: Penn State, 2011).

- Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses (New York: Routledge, 1992), quote on 65.

- Lambert Daneau, A Dialogue of Witches (London: East, 1575), quotes on 32-35.

- Thomas Watson, The Beatitudes (London: Smith, 1671), quote on 112-113.

- Pedro Cieza de León, [La chronica de Peru. Part 1] Chronica del Peru ... (An Anvers [Antwerp]: En casa de Martin Nucio, 1554), illustration; verso leaf 40. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. For fear of bodily alterations in imperial worlds see, Karen Kupperman, "Fear of Hot Climates in the Anglo-American Colonial Experience," WMQ 41, 2 (1984), 213-240; Joyce Chaplin, "Natural Philosophy and an Early Racial Idiom in North America: Comparing English and Indian Bodies," WMQ 54 (1997), 229-252; Suman Seth, Difference and Disease: Medicine, Race, and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge, 2018); Mark Harrison, “’The Tender Frame of Man’: Disease, Climate, and Racial Difference in India and the West Indies,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 70 (1996), 68-93; Katherine Johnston, “The Constitution of Empire: Place and Bodily Health in the Eighteenth Century Atlantic,” Atlantic Studies 10, 4 (2013), 443-466; Manuel Barcia, The Yellow Demon of Fever: Fighting Disease in the Nineteenth-Century Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven: Yale, 2020).

- Thomas Herbert and William Marshall, A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile Begunne Anno 1626 (London: Stansby and Bloome, 1634), quotes on 6–8.

- Ralph Bohun, A Discourse Concerning the Origine and Properties of Wind (Oxford: Hall, 1671), quotes on 203–204.

- Lionel Wafer, and George Parker Winship, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America (Cleveland: Burrows, 1903), quotes on 46, 100.

- For example, see, Robert Hayman, Qvodlibets: Lately Come Over from New Britaniola (London: Elizabeth All-de, 1628), 11, 59.

- Stuart Schwartz, Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina (Princeton: Princeton). See also the emergence of free trade due, in-part, to the ever presence of hurricanes within, Sherry Johnson. Climate and Catastrophe in Cuba and the Atlantic World in the Age of Revolution (Chapel Hill: North Carolina, 2011).

- Schwartz, Sea of Storms, 14-16; Kathleen Ann Myers, Fernández de Oviedo's Chronicle of America: A New History for a New World, translations by Nina M. Scott (Austin: Texas, 2010), quotes on 175.

- Myers, Fernández de Oviedo's Chronicle of America, quote on 175; Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Sumario de la natural historia de Las Indias, Biblioteca Americana. Serie de Cronistas de Indias 13 (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1950 [1526]), quotes on 124-125.

- For more on labor acquisition see, Kris Lane, “Africans and Natives in the Mines of Spanish America,” in Beyond Black and Red: African-native Relations in Colonial Latin America, ed. Matthew Restall (Albuquerque: New Mexico, 2005), 139-184.

- Peter Martyr D'Anghera De Orbe Novo, Volume 1 (of 2) The Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera, trans. Francis Augustus MacNutt (New York: Putnam's Sons, 1912 [1516]), quotes on 111-112.

- Martyr, De Orbe Novo, Volume 2 (of 2) The Eight Decades, 274-276; Theodor de Bry, “Valboa throws some [Indigenous people], who [were perceived to have] committed sodomy, to the dogs to be torn apart,” in America, Part Four. Distinguished and admirable history of Western India, Discovered for the first time by Christopher Columbus in the year 1492. Written by Jerome Benzoni from Milan, Who having lived there for fourteen years, Diligently observed everything. Additions to almost every chapter, not including comments, Also treat the idolatry of those populations. Also added is a map of those regions. All illustrated with elegant images copper engraved by Theodor de Bry from Liege, Citizen of Frankfurt (Frankfurt: De Bry, 1594).

- William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World (London: Napton, 1699), 131-133.

- Thomas Gage, The English-American (London: Cotes, 1648), quotes on 183.

- For terminology on Anthropocene and Capitalocene see, Jason Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015). Image from, Pieter Vander Aa, Naaukeurige versameling der gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indiën ... zedert het jaar 1524 tot 1526 (In het ligt gegeven te Leyden [Leiden]: Door Pieter Vander Aa, boekverkoper in de St. Pieters Koor-steeg, in Plato, 1707), fold-out plate; vol. 15, [part 2], following p. 128. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

- The Spanish letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant' Angel, Escribano de Racion of the Kingdom of Aragon, dated 15 February 1493, trans. M.P. Kerney (London: Quaritch, 1893); Girolamo Benzoni, De gedenkwaardige West-Indise voyagien, gedaan door Christoffel Columbus, Americus Vesputius, en Lodewijck Hennepin. Behelzende een naaukeurige en waarachtige beschrijving der eerste en laatste Americaanse ontdekkingen, door de voornoemde reizigers gedaen, met alle de byzonders voorvallen, hen overgekomen. Mitsgaders een getrouw en aenmerkelijk verhaal van de opperhoofden der Spanjaarden onderlinge oneenigheden doenmaals in America, trans. Pieter Vander Aa (Te Leyden: Pieter Vander Aa, 1704), fold-out plate; part 1, following p. 64. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

- Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-1700 (Stanford: Stanford, 2006), quote on 33.

- Theodor de Bry, [America. Pt 3. Latin] Americae tertia pars memorabile[m] provinciae Brasiliae historiam contine[n]s ...(Frankfurt am Main] Theodori de Bry, 1592), illustration, p. 223. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library; Hans Staden, Wahrhaftige Historia ... in der Newenwelt America gelegen (Marburg: Staden, 1557); Hans Staden, Hans Staden's true history: an account of cannibal captivity in Brazil, trans. Neil L. Whitehead, and Michael Harbsmeier (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008); Jean de Léry, History of a voyage to the land of Brazil, otherwise called America: containing the navigation and the remarkable things seen on the sea by the author; the behavior of Villegagnon in that country; the customs and strange ways of life of the American savages; together with the description of various animals, trees, plants, and other singular things completely unknown over here, trans. Janet Whatley (Berkeley: California, 1990). For the influence of De Bry and his sons on concepts of Native Americans within European printing see, Michael Gaudio, Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2008). See also, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics (Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2015).

- David Livingstone, “Race, Space and Moral Climatology: Notes Toward a Genealogy,” Journal of Historical Geography 28, 2 (2008): 159–180.

- Andrés Pérez de Ribas, History of the Triumphs of Our Holy Faith Amongst the Most Barbarous and Fierce Peoples of the New World, trans. Daniel Reff (Tucson: Arizona, 1999), quote on 189-190.

- Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón, Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that Today Live Among the Indians Native to this New Spain, 1629, ed. and trans. James Richard Andrews (London: Oklahoma, 1984), quotes on 62-63, notes on 112, 330. Demons would also often be perceived within early Spanish churches in South America, where many would be heard barking like dogs, braying like bulls, and hissing like serpents. See this battle over the soundscape concerning demonic noises, especially concerning the Guarani, within, Jutta Toelle, “Mission Soundscapes: Demons, Jesuits, and Sounds in Antonio Ruiz de Montoya’s Conquista Espiritual (1639),” in Empire of the Senses: Sensory Practices of Colonialism in Early America, eds. Daniela Hacke and Paul Musselwhite (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 67-87.

- Bernal Diaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain, trans. J. M. Cohen (New York: Penguin, 1963), quote on 123. See also, the Aztec Death Whistle, a musical instrument in the shape of a skull said to release the sound of all the dead sacrificed in the Aztec empire, to impose fear to enemies before battle and to represent the dead on the Day of the Dead celebrations within, Dominic Pettman, Sonic Intimacy: Voice, Species, Technics (or, How to Listen to the World) (Stanford: Stanford, 2017), 83-84.

- Although the Black Legend became prominent in English justifications for colonization throughout the New World and especially with the Western Design, many scholars have pointed to the continuous borrowing of cultural and religious rhetoric between Protestant and Catholic nations when focusing their linguistic force upon the creation of a subaltern other in the early stages of colonialism. Cañizares-Esguerra, Puritan Conquistadors, 1-119. See also, Susan Juster, Sacred Violence in Early America (Philadelphia: Penn, 2016), 110-123.

- Fernando Cervantes, The Devil in the New World: The Impact of Diabolism in New Spain (New Haven: Yale, 1994), quotes on 116-118; Andrew Redden, “Vipers under the Altar Cloth: Satanic and Angelic Forms in Seventeenth-Century New Granada,” in Angels, Demons and the New World, eds. Fernando Cervantes and Andrew Redden (Cambridge: Cambridge, 2013), 146-170.

- Weekly Memorials for the Ingenious; or, an Account of Books Lately Set Forth in Several Languages. With Other Accounts Relating to Arts and Sciences. No. 1-50 (London: Faithorne and Kersey, 1682), quote on 86.

- Herbert, A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile, quote on 212.

- George Pinckard, Notes on the West Indies (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1806), esp. 206-208; Henry Fitzherbert, “The Journal Henry Fitzherbert Kept While in Barbados in 1825,” JBMHS 44 (Nov/Dec, 1998): 117-191, esp. 132-133.

- Gage, English-American, quote on 23.

- Lauric Henneton, “Introduction: Adjusting to Fear in Early America,” in Fear and the Shaping of Early American Societies, ed. Lauric Henneton and L. H. Roper (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 1-37.

- Richard Godbeer, The Devil's Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge, 1992), 91-97.

- Craig Koslofsky, “Offshoring the Invisible World?: American Ghosts, Witches, and Demons in the Early Enlightenment,” Critical Research on Religion (2021): 1-16, quote on 11.

- Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relacion de reyno de Chile] Historica relacion del reyno de Chile, y delas missiones, y ministerios que exercita en el la Compañia de Iesus (En Roma [Rome]: Por Francisco Cavallo, 1646), plate; following p. 302. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

- Johann Friedrich Schröter, Siegmund Jakob Baumgarten, Joseph-François Lafitau, and Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix. Algemeine Geschichte der Länder und Völker von America.: Erster [-zweiter] Theil (Halle: Bey Johann Justinus Gebauer, 1752), plate 15; vol. 1, following p. 160. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

- Kris Lane, Potosi: The Silver City That Changed the World (Berkeley: California, 2019), quotes from 105-106. See also, Jason Moore, “‘This lofty mountain of silver could conquer the whole world’: Potosí and the Political Ecology of Underdevelopment, 1545-1800,” Journal of Philosophical Economics IV, 1 (2010), 58-103.

- Image from, Girolamo Benzoni, Americae pars quinta nobilis & admiratione (Frankfort: De Bry, 1595), part V, fig 1. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. See also, the racialization linked to mining language, miners, and metal within, Allison Margaret Bigelow, Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Williamsburg: Omohundro, 2021), 259-293, and the colonialist language of Scholasticism, “metaphysical instrumentalism,” and legalist justifications for violent forms of mining in early South America within, Orlando Bentancor, The Matter of Empire: Metaphysics and Mining in Colonial Peru (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, 2017). See also, Ralph Bauer, The Alchemy of Conquest: Science, Religion, and the Secrets of the New World (Charlottesville: Virginia, 2019), June Nash, We Eat the Mines and the Mines Eat Us: Dependency and Exploitation in Bolivian Tin Mines (New York: Columbia, 1993); John Tutino, Making a New World: Founding Capitalism in the Bajío and Spanish North America (Durham: Duke, 2011).

- Diego Valades, Rhetorica christiana ad concionandi, et orandi usum accommodata (Perusiae: Apud Petrumiccobum Potrutium, 1579), plate; following p. 281. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

- For more on concepts of race and the senses see, William Tullett, "Grease and Sweat: Race and Smell in Eighteenth Century English Culture," Cultural and Social History 13, 3 (2016), 307-322; Mark Smith, "Transcending, Othering, Detecting: Smell, Premodernity, Modernity," Postmedieval 3, 4 (2012): 380-390.