Wind as Style

A Chinese Aesthetics Perspective

Li Xu with illustrations by Panpan Yang

“ The wind is invisible, but we can feel its existence and ubiquity, or wind is a sensible form of air.”

Volume Two, Issue Three “Wind,” Essay

Perceptions and depictions of wind are not universally interchangeable; cultural significations and philosophies forge distinct interpretations of wind that can permeate everyday linguistic and aesthetic expressions. How does the depiction of wind in art, for example, reflect these interpretations? From agriculture to medicine, from light to the multifarious notion of qi, Xu weaves various forms of Chinese cultural understandings of wind with Merleau-Ponty's notion of the "flesh" of the world. Panpan Yang's fluid image shows the intangible yet very present "gesture of the wind", mirroring Xu’s contemplation of wind as a key symbol in Chinese language, philosophy, and cultural aesthetics.

Polysemous Wind

Wind is a common word with a long history in the Chinese language. Wind is referred to as Feng in Chinese. Over 200 Chinese words have been associated with Feng, most famously Fengshui, a geomantic omen that means “wind-water.” In ancient Chinese tradition, wind and water are among the most fundamental elements in life. Notions of “wind” and “water” around the living environment and its arrangement directly affect a household’s life and fate. Other terms that include the concept of wind are Fengguang (wind light, beautiful scenery), Fengjing (wind scene, landscape), Fengge wind character, style) are important concepts in Chinese aesthetics. François Jullien once wrote, “Wind (Feng) as an endless force of dissemination and animation, is one of the richest notions of Chinese thought, and one of the most ancient.”1 Despite being invisible, the wind is ubiquitous both as a cultural and a natural phenomenon. It appears in aesthetic contexts, such as music, literature, and art. Weili Zhao argues, “The Chinese character of wind is bound to other Chinese characters to form a sensitivity to the complex movements of thought and cultural practices. Wind is a cultural and historical way of being.”2 I will briefly introduce the rich connotations of wind at different levels to get a glimpse of the complex network of meanings behind it, creating an aesthetic image of the gentle exploring how Chinese traditions perceive, understand and express wind, reflecting cultural style.

As a natural phenomenon, wind plays a vital role in ancient Chinese agricultural society. Chinese aesthetician Fa Zhang writes, “Regarding the nature of the wind, its core revolves around the calendar, and the calendar, in turn, is closely related to the earliest fishing and hunting activities and later agricultural production.”3 Wind has a seasonal nature and is related to astronomical meteorology, and for this reason, indicates and determines agricultural production. In Chinese, the wind is named according to its direction; there are four winds respectively from the west, the east, the north, and the south. It then evolves into eight winds, from the southeast and northwest wind, which generates the eight diagrams as alterations in the wind reflect the universe's operative laws. It is believed that the arrival of the wind from all directions repeats, and wind indicates the changes of seasons. This eventually led to the development of the Chinese calendar.

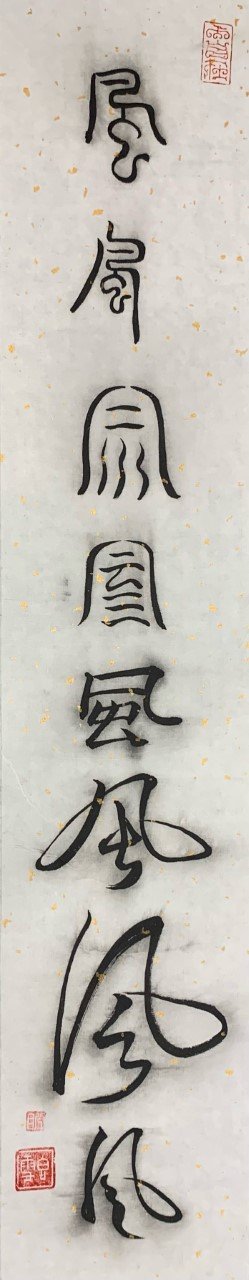

Wind is also connected to the magical bird of phoenix. There is a striking similarity between the two characters of wind and phoenix, and their pronunciations in Mandarin are almost the same (Figure 1). Although wind is a natural phenomenon, it holds mystical and mythological significance in Chinese culture. While the wind manifests the law of the universe in an invisible yet sensible way, the image of phoenix is often depicted as riding the wind, symbolizing the ideal of spiritual transcendence of wind. According to Fa Zhang, if the wind was considered as a kind of divine force combining nature and divinity, then the phoenix is the embodiment of the divine force of the universe in the form of a specific animal.4 Additionally, the phoenix is also believed to be the symbol of the element of fire, which is generated by wind. Fire and wind are essential elements for creating and sustaining life and vitality, both are seen as complementary elements in the Chinese cosmological worldview and reflect Chinese cosmic structure.

Figure 1: Panpan Yan, Phoenix (2022)

Moving from the cosmological to the psychological, wind has symbolic ramifications on personality. Wind is often used as a metaphor for the character of a nobleman. For example, Confucius uses wind and grass to describe these types of personalities: “The virtue of the gentleman is like the wind; the virtue of the small man is like grass. Let the wind blow over the grass and it is sure to bend.”5 In this metaphor, the virtue of a gentleman is like the wind, which has a wide influence with high integrity among people, just as the wind has the power to influence.

There is also a deep connection between wind and music. The wind is believed to create sound and music, or currents and objects strike each other to produce sound. There would be no sound or music without wind or air movement. The wind is the flow of air, passing through different cavities to create various sounds. Consider musical instruments: the wind flows through the instrument and vibrates at different frequencies to produce different sounds. There is no sound when the wind stops.

As a concept, wind also plays into developments in Chinese medicine. The wind can attack the human body and cause disease, invading bones, meridians, and joints. A physical illness moves like the wind in the way that small changes trigger more changes. “Wind is associated with movement; its attack is varied and fast and is often recognized by signs like pain that moves from one place to another.”6 It is not easy to control the wind, just as it is challenging to determine the cause of some diseases. And yet, the wind is also used to understand and diagnose various illnesses. For example, the Chinese term of stroke is Zhongfeng (struck by wind). Wind is also combined with other pathogenic factors, for instance, Fenghan (wind cold) is used in Chinese medicine to describe symptoms such as chills and fevers, similar to the symptoms when one catches a cold in Western medicine.

Wind is a common word in Chinese, but it is also a root word that can reproduce across many fields of knowledge. As one of the most common words, wind is also one of the most difficult words to translate into other languages, as it has complicated and ambiguous meanings. As Lu Shuyuan wrote, “The semantic field of ‘wind’ radiates to various fields of ancient Chinese philosophy, agriculture, medicine, sociology, ethics, psychology, literature and art, geomantic omen (or fengshui, modern people call it ‘eco-architecture’). It integrates the human subject with its living environment and all aspects of human existence into a harmonious, unified and vibrant system.”7 As Julien says, every school of Chinese thought ceaselessly exploited the imagination of wind.8 The varieties of combinations related to “wind” show how this element, in theory, practice, and concept, is significant in Chinese aesthetics and culture.

Wind and Style

One of the most prominent meanings of wind in Chinese culture relates to aesthetic style. Feng is often used to describe the characteristics or general perceptions of a certain thing, and it is also associated with different regions, classes, arts, and cultures. For example, Tang Feng means the style of the Tang Dynasty, and is used when a work of art has the unique style and cultural atmosphere from this period in time. In recent years, Guo Feng (national wind, or national style) is often used in contemporary mainstream pop culture in Chinese context. People in many fields, including music, dance, fashion, and so on incorporate traditional Chinese culture into pop culture. To add just one more example, the term “School wind” refers to a general atmosphere and style of a school. Zhao reinvested the Chinese term Feng with its cultural reference and linked “wind” and “education” in cross-cultural studies. Zhao treated “these wind-terms as linguistic metaphors and interpret-translate[d] them as school atmosphere, teaching manners, and learning styles.”9 The word “wind” as style has been commonly used in contemporary Chinese culture, which reflects the appreciation of the cultural heritage of the word “wind” and how wind has demonstrated its vitality in modern Chinese language.

Since the wind has the power to move people, it also has pedagogical meaning in terms of art. Works of art can educate people, affect their emotions, and lead them to improve their behavior and conform to particular customs. This is also how the wind works: it is invisible, but people can feel its affects and effects. Wind thus symbolizes a way of teaching. Wind, in the earlier history of Chinese culture, means “ballad” or refers to folk songs; when these are passed down through generations, they are described as moving as if through the wind.

The wind is also used as the main criterion for evaluating and criticizing literary works, especially poetry. Fenggu, which literally translates to “wind-bone,” is used to describe a work of art with a unique style: feng means “style,” and gu refers to content, structure, thought, and logic. Fenggu emphasizes robust and vigorous contents and structures, as well as impact and affect in the expression of the work of art. Other terms associated with wind, such as Fengshen (Wind god), Fengzi (Wind gesture), Fengyun (Wind charm), Fengcai (Wind color) collaborate with the perception of wind and how it resonates with the appreciation of art. All these words have Feng (wind) simply because the wind is considered to be one of the main causes of human feelings. When one judges and appreciates a work of art, such as Chinese calligraphy or a painting, the term Fenggu is often used to refer to the vigor and style of the work of art. When a work of art is described as having Fenggu or Fengshen, it means they are created in a unique style with lucid and vigorous content through powerful expression. (Figure 4) Fenggu and Fengshen refer to the artist’s personality and style, with a sense of social responsibility. The wind is used to connect the artist's style and the work of art; because they penetrate everything, the wind, and air, as vital forces, transform the work of the artist from its conception to creation. It is believed that the moral character and artist’s style determine the merit of a work of art as the use of the brush through the body as the wind blows.

Wind and Air

When discussing wind, it is necessary to relate it to air, that is, Qi. In Chinese thought, the wind is perceived as a natural force and one manifestation of the movement and flow of Qi in the world. Qi is often translated as “air” and has diverse meanings. Qi is the most fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy and aesthetics. Air is a term, a category, and a system of understanding the cosmos. In ancient Chinese tradition, the air was the origin of everything and an uncertain and ambiguous condition that had the potential to generate everything. The air resonates breath, the breath of life; atmosphere; transcendent vital force. Air has been transformed from the basic to the most abstract, from the physical and natural world to the physiological and spiritual fields, and the element of being in the universe. In Chinese culture, everything in the universe emerges from the power of Qi, including human beings, objects, life, and so on.

The universe is full of air. Air does not have a specific shape, and all solids and liquids can be turned into Qi, and vice versa. Ancient Chinese tradition believed that the physical world is a continuous whole that consists of Qi which coalesces into sensible things, for example, wind (Figure 2). The wind is considered to be one of the most essential manifestations of air. Wind and air are interconnected and used together to describe the world's energy flow.

Figure 2: Panpan Yang, Wind and Air (2022)

In its expanded sense, air can be considered abstract wind, which is more diffuse and cosmic than perceptual wind in everyday life. The wind is invisible, but we can feel its existence and ubiquity, or wind is a sensible form of air. François Jullien describes the wind thusly: “The wind is truly the invisibility at the limit of the sensible that makes us experience the sensible. Its influence is all the more profound in that it has no opacity, its reach and penetration are all the vaster in that, itself dissipated, it cannot be completely identified.”10 Wind is similar to air because wind and air are manifestations of the same force, just with two different names: wind is the flow of air, and air is constantly changing and in motion and does not have to take on a specific “shape” as in common, average everyday wind currents. It is the movement of air that generates wind and causes everything to appear. In its most primordial sense, in the tradition of Chinese aesthetics, it is believed that the convergence of air currents or wind gives life and shapes to all things. The term Fengqi (Wind air) was later created to describe the collective attitude, values, and behaviors that demonstrate the intangible yet powerful influence of cultural norms, practices, and traditions that penetrate daily life through the power of wind and air.

Wind, with its meanings related to style, and its relationship to Qi, echoes the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of flesh. Unlike ancient Greek philosophers who used natural objects as an organizing concept, Merleau-Ponty uses the term “flesh” to describe the unity of the universe. Flesh is a central notion of Merleau-Ponty’s thought, and he emphasizes how flesh becomes more ontologically primary and situates both body and world within its folds. Flesh, in this sense, is the prototype of Being. He states that, “what we are calling flesh, this interiorly worked-over mass, has no name in any philosophy. As the formative medium of the object and the subject, it is not the atom of being, the hard in itself that resides in a unique place and moment.”11 It is worthy to note that in both East and Western cultures, philosophers used basic elements such as water, fire, and dirt to abstract the nature or essence of the universe, and conceptions of the flesh complement these ideas.

Flesh is also considered to be an ontological element, like air. It is not visible, tangible, or sensible, and it exists above and below the immediate sense perception. “The flesh is not matter, is not mind, is not substance. To designate it, we should need the old term ‘element’ in the sense it was used to speak of water, air, earth, and fire, that is, in the sense of a general thing,”12 Merleau-Ponty argues, adding that “we must think it, as we said, as an element, as the concrete emblem of a general manner of being.”13 On a metaphysical level, both flesh and air are understood as the basic element of beings, referring to the vital force of the universe. If, as Merleau-Ponty says, style is the fragment of being, then we can understand wind as a trace of air. Wind manifests invisible air through its configuration; invisible and intangible, it shapes perceptions and understandings of the world in Chinese thought.

Wind and Light

Here, I would like to emphasize that there are differences and similarities between Merleau-Ponty’s idea of style and wind as style in Chinese thought. To explore the different understanding of style and the world, we should use culturally specific approaches to exemplify natural things, such as air, wind and light.

Wind touches us as the style of certain things strikes us. One cannot grasp the wind and explicitly explain what it looks like. Style, as an overall perception, can only be a vague impression. As Tonino Griffero says, “wind is always a mediated and thus indirect manifestation.”14 Wind and air do not have a particular shape and change as part of an unknown and mysterious existence. Both flesh and air are ineffable and imperceptible; the perception of wind leads us to ambiguity and a sense of inexhaustibility. The nature of wind and air determines the aesthetic features with the interaction and transformation between real and virtual, visible and invisible, existence and absence, substance and void.

Moving beyond the Chinese aesthetic understanding of wind, it is important to note how Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology emphasizes vision and visibility when speaking of flesh. More specifically, flesh is defined through the invisible. He writes, “It is this visibility, this generality of the Sensible in itself, this anonymity innates to myself that we have previously called flesh, and one knows there is no name in traditional philosophy to designate it.”15 The role of light, as a visual and phenomenological concept, is also significant in this regard. According to Merleau-Ponty, we see things with light and according to light. Light is a prerequisite for vision and visibility: “Like the light, these levels and dimensions, this system of lines of force, are not what we see; they are that with which, according to which, we see.”16 Light makes it possible for us to see things or for things to appear and become visible to us. Put simply, light contributes to the visibility and the appearance of all things. In a certain sense, we can argue that the flesh is like light insofar as both things emerge out of an appraisal of the style of the wind.

Figure 3: Panpan Yang, Evolution of Chinese characters of Wind (2022)

Like the wind, in Chinese aesthetics, light is an aesthetic prerequisite for perceptions of the world. It is no coincidence that the Chinese use the term “wind and light,” to describe the phenomenal world: Fengguang. According to Cheng J. Liu, “Light and wind are the original tangible things to manifest themselves to man, the former makes things visible, and the latter makes the world audible,” adding that wind and light become “the initial regulations of everything as phenomenal existence.”17 Liu also states that if light makes the world statically visible, then wind works dynamically to move things and make them sensible. As Liu argues, “in classical Chinese aesthetics, the so-called aesthetic world is also the phenomenal world where wind and light interact.”18 Similarly to Merleau-Ponty’s intertwining of flesh and the visible, in this conception, wind and light function in different ways and interact together for the possible sensible world.

Since air is the origin of everything, and wind is the moving air, when wind and light interact, there is a sense of ambiguity in the light as well as in the air. Air exists between the visible and invisible. If we take landscape painting as an example, in Chinese landscape painting, there is no light, or the light is not visible or explicit, which is different from traditions in Western landscape paintings. Here, light conceals itself in the air. Wind and light fuse into each other and create a sense of ambiguity, which indicates one feature of Chinese aesthetics.

Light, in Chinese aesthetics, is not only ontological but also functional. Light is not something tangible that we are meant to grasp, but a fundamental existence that makes things visible. It is the prerequisite for things to reveal themselves and appear to us. Light travels between the visible and the invisible, Yin and Yang, and nothingness and existence. Light conceals itself in water, clouds and air.

Light is related to vision, yet vision is not the dominating sensation in Chinese culture. Although no hierarchies of sensation exist in Chinese tradition, wind is a better symbol of representation than light. One can hear the wind, smell the wind, and feel the wind. The subject perceives by interconnecting the sensations with a whole. While in Chinese aesthetics, the wind is a significant example that demonstrates different approaches to sensibility. This differentiation illustrates the uniqueness of Chinese wind aesthetics as a particular style of flesh (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Panpan Yang, Wind, Light and Phoenix (2022)

Conclusion

Chinese style is expressed through wind and this unique style offers something different in terms of the discussion of “atmosphere” and aesthetic environmentalism in the West. The way Chinese tradition understands, perceives, and expresses the wind is closely related to perceptions of its cosmos, as it affects aesthetic attitudes towards natural objects. Basic elements of the natural environment, such as wind, air, and light, offer alternative ways of aesthetically perceiving and appreciating the world. The configuration and connotation of the wind, and the diversity and humanities of wind have contributed to the acculturation of both wind and nature. Like wind itself, the study of wind touches and penetrates many fields. The present article may blow through and across multiple adjacent topics, but my writing embodies winds intentionally or unintentionally, as I am writing in a windy style; like a breeze. The idea of wind touches me as the wind blows over me. Wind, as Tonino Griffero writes, “has always been the object of human attempts to catch it and exploit its power.”19 My perception, understanding and writing of wind are attempts to capture its gestures or fragments (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Panpan Yang, The Gesture of Wind (2022)

❃ ❃ ❃

Bio

Li Xu received her Ph.D. in philosophy from Beijing Normal University in China in 2019. Currently, she is pursuing her second Ph.D. in Art Education at the University of North Texas, USA. Her research interests include aesthetics, phenomenology, intercultural and ecological art education, and interdisciplinary studies.

Panpan Yang, is an artist with specialties in Chinese traditional painting and digital art. She focuses on media and their transformation in art. She is getting her Ph.D. in art education at the University of North Texas, USA. Her research interests include community-based art education, intergenerational art education, and social justice in art education.

- François Jullien, The great image has no form, or on the nonobject through painting (University of Chicago Press, 2009): 41.

- Weili Zhao, China’s education, curriculum knowledge and cultural inscriptions: Dancing with the wind (Routledge, 2018): xv.

- Fa Zhang, “The Characteristics of Chinese thinking and aesthetics embodied in Feng and Feng as the same character.” Social Science Series 1:8 (2016): 156.

- Zhang, “The Characteristics of Chinese thinking and aesthetics,” 155.

- Din Cheuk Lau, The analects (Penguin, 1979): 115–16.

- Mehrab Dashtdar, Mohammad Reza Dashtdar, Babak Dashtdar, Karima Kardi, and Mohammad khabaz Shirazi. “The concept of wind in traditional Chinese medicine,” Journal of Pharmacopuncture 19:4 (2016): 293.

- Shuyuan Lu, “The Semantic Field of the Chinese Character ‘Wind’ and the Spirit of ancient Chinese Ecological Culture,” Literary Review 4 (2005): 10.

- Jullien, The great image has no form, 41.

- Zhao, China’s education, 3.

- Jullien, The great image has no form, 41–42.

- M. Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible (Northwestern University Press, 1968): 147.

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 139.

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 147.

- Tonino Griffero, “It Blows where it Wishes: The Wind as a Quasi-Thingly Atmosphere,” Venti Journal 1:1 (September 2020): 34.

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 139.

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, li.

- Chengji Liu, “Objects, Light and Wind in Classical Chinese aesthetics,” Journal of Seeking Truth 5:6 (2008): 102.

- Liu, “Objects, Light and Wind in Classical Chinese aesthetics,” 103.

- Tonino Griffero, Quasi-things: The paradigm of atmospheres (Suny Press, 2017): 9.

Suggested Reading