Breathing Worlds

Derek McCormack and Lucy Sabin

“The machine will tell you what to do, he says. Just breathe normally until then.”

Volume Two, Issue One, “Inhale/Exhale,” Essay

Bernard de Fontenelle, Illustration from Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes, 1686. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source.

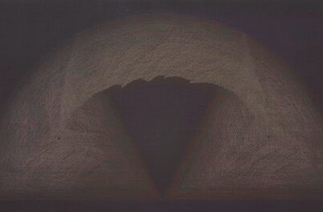

It can feel as if we each live in our own worlds, even if only in our own imagination. Bernard de Fontenelle illustrates the planets of our solar system, each as their own galaxies with moons and other orbiters. Stacked on top of each other, the image seems to contain one world and a multitude of worlds simultaneously. Lucy Sabin and Derek McCormack discuss this plurality of existence in relation to breath, their essay combining a recollection of Sabin’s project for Museum Art Oxford, Breathing worlds, and McCormarck’s scholarly and personal experience with lung CT scans in the midst of a global pandemic that affects the respiratory system. While each person lives their own life and has their own experience of breathing, Sabin and McCormack illuminate how the breath is both a personal and universal experience.

- The Editors

Inhalation

Breathing has resurfaced as a refrain across many of the elements of experience and political life with which the humanities and social sciences are concerned. There is growing awareness of how the conditions of the air in which bodies are implicated and to which they are exposed are changing as a result of anthropogenic processes operating at a range of spatial and temporal scales.1 There is greater attention to how the distribution of exposures to these conditions intersects with multiple and ongoing forms of structural and systemic violence.2 And there is a renewed commitment to the cultivation of collective capacities and rights to breathe across different forms of human and more-than-human life as a vital focus for political orientations.3 COVID-19 is influencing these developments in urgent ways. Critically, the pandemic is a reminder to those of us who had the privilege of forgetting, that breathing cannot and should not have been taken for granted as a rhythm of worldly participation.

In this contribution, we draw upon our experiences leading up to a collaborative, breath-centric project with Modern Art Oxford in 2020. For Lucy, this interdisciplinary collaboration built upon Breathworks, a participatory arts project that preceded and evolved during the pandemic.4 Her strand in this paper probes breathing in relation to media practice and theory by exploring conceptualizations of breathing in terms of participation and interfacial relations. For Derek, this collaboration was oriented initially by research interests in atmosphere, air, and questions of elemental envelopment. In the context of the pandemic, however, his participation became tensed by the ongoing experience of symptoms shared by many others, possibly of Long Covid,5 symptoms that stretch out into a variable, ill-defined, but frustratingly persistent and intrusive modification of breath. His autoethnographic fragments draw attention to moments in which this experience is exposed to the scrutiny of medical devices for testing, measuring, and scanning bodily capacities, volumes, and effort. We describe the dual process of arriving at our collaboration, with the interfaces between our contributions becoming more porous as the piece unfolds. In concluding, we dwell briefly on the idea of breathing worlds as a process and noun that gestures both to the conditions in which breathing takes place and to the labor that goes into making and modifying these conditions.

Participation

Early April, 2020. First time out of the house for weeks. New rules of engagement, of distancing, approaching, and passing with care. You almost make it to the end of the street. And then he comes around the corner, vaping. He crosses the road just in front of you. In the cold air his breath leaves a mist, hanging there, hardly dispersing. To walk on will be to walk through. Aerosol. To continue will be to be exposed to his cloud of exhalations. Turning quickly, you begin walking home. But not fast enough to avoid the faint, sickly sweetened scent of an unwanted molecular intimacy.6

***

In December 2019, I was appointed ‘Creative Associate (Digital)’ at Modern Art Oxford. My task during the associateship was to engage the gallery’s online audiences via a digital participatory arts project. In January 2020, when COVID-19 was only on the periphery of news media in the UK, the commissioning curator Andrée Latham and I held our first meeting to firm up a theme for the project. While a few cards were laid on the table, we soon realized that both of us were fascinated with the theme of breathing. We bonded over our respective experiences of conscious breathing for managing the ups and downs of life and wondered: What if we were to design a participatory project that inquired after, made palpable, and expressed people’s relationships with breathing? Led by creative curiosity as well as a concern that any meaningful public engagement should be designed according to an inclusive range of breathing experiences, we began to sound out opinions by setting up some focus groups that would become central to the development of Breathworks.

Each focus group member was either a regular volunteer at the gallery or had responded to an open invitation via the gallery’s communications channels. And each arrived with personal histories and patterns of breathing that preceded and gave meaning to our encounters. As we discussed respiratory matters and responded to some examples of community exhibitions that might allow space for capturing unique experiences of breathing, it became apparent that “participants” or “users” were, first and foremost, breathers.7 The intensities of living, the attentiveness to happenings, and the key to immersing oneself during the focus groups hinged upon shared yet unique experiences of breathing.8

The acknowledgement of difference among breathers both within and beyond the focus groups, which were limited by number and sample, was essential to creating a breathing space or “conspiracy” for cultivating breath through a collective of voices.9 Timothy Choy leans into the etymology of conspiracy (lit., “breathing with”) to invoke a political “commitment to breathing together from and in an unequally shared milieu.”10 As a political term for being both embodied and in-common,11 conspiracy maps onto the diverse field of participatory arts — ”forms of artistic expression which enable shared ownership of decision-making processes and often aim to generate dialogue, social activism, and community mobilization.”12 As conspiracy, breathing is an ongoing chorus of multiple voices.13

Interface

September 9th, 2020. The radiology department at the Churchill hospital. A CT (CAT) scan of the lungs. He asks you to lie down. Takes an arm, finds a vein, describes the procedure. The machine will tell you what to do, he says. Just breathe normally until then, he says — an instruction that has the same effect as someone asking you to walk normally across a room while watched by an audience. The platform slides you through the circular portal of the scanner. There is a synthetically voiced instruction from the machine: “Hold your breath.” You stop immediately, midway through an out-breath, eager to obey this disembodied authority. You hold this x-rayed pause until the voice instructs you, once again, to breathe…

***

As Breathworks began taking shape in the spring and early summer of 2020, background events became the foreground. Pre-existing instances of breathlessness, caused by intersecting systemic violences, became more palpable and more acute.14 The Breathworks focus groups gained newfound urgency and conversations turned to the outside world. Outside got inside, to paraphrase Kate Bush’s 1980 track, Breathing. In response, instead of overdetermining how Breathworks would respond to recent events, there was a determination to safeguard breathing space in the public invitation to participate, not least by keeping our definition of breath itself open to creative interpretation.15

Figure 1. Sample of contributions to Breathworks. Credit: Lucy Sabin.

The “submissions” webpage for Breathworks, which I designed with input from other breathers in focus groups and subsequent usability tests, invited people to submit an image, a sound recording (20-60 seconds) and a short description “to capture an experience of breathing.”16 At the receiving end, the digital team at Modern Art Oxford composited visuals with audio by superimposing an animation in the form of a circular sound wave to produce moving image files that resembled each other in their pulsating presence but clearly derived from different sources (Figure 1). During a public open call throughout the month of August 2020, we gathered responses over multiple communications channels. The community exhibition came to resemble windows onto a series of breathing worlds, all attuned to atmospheric happenings from different coordinates:

Participants followed breathing along a number of threads, including the volume of air inhaled or exhaled; the paralinguistic expressiveness of gasps and sighs; reconnecting with self and nature (plants, the ocean); cosmological narratives about breath as life force; confronting climate change and forest fires; breathing beneath and through a face covering; machinery that ‘breathes’ (from fridges to rotary fans); an ephemera of birdsong, shadows and blurred images; experiencing health conditions as labored breath; and suspending breath in poetry and blown ink.17

As a process-driven online exhibition, Breathworks revolved around the creation, noticing, and convergence of different interfaces for “making breath visible” beyond biomedical paradigms.18 Originating in fluid dynamics, an interface is a concept in environmental and new media that describes the emergent property of becoming together at a particular zone or “boundary condition.”19 The term is often deployed within human-computer interaction (HCI) as a synonym for the frontend layout or screen that reciprocally responds to the user’s responses, hence the emphasis on making visible by connecting something less legible (e.g., backend code) with an “intuitive” display. Yet the processual interface predates and will outlive such sites of amplification.20 For there is a subtle but fundamental difference between screen and interface in the first place: a screen only becomes an interface by “coupling” with a user.21

An interface is a zone made liminal through animating interactions, an unfolding envelope of affective experience.22 Such an amorphous condition only emerges through processual togetherness, rather than defining an a priori fixed separation between one level of complexity and another.23 Taken thus, as environmental media, the interface concept can designate the liminal zone between elemental milieux (e.g., water/sky) or between bodies and the air — things that compose one another.24 Operating in this zone, breathing technologies from spirometers to gas masks give rise to interfaces that blend environmental and new media in order to generate medical information or a (more) breathable interstice.25

***

October 9th 2020. Again the Churchill hospital, Oxford. Respiratory Outpatients. A lung function test. This test — or tests — seem more involved, interactive, participatory. An invitation to breathe into a small, handheld device. A FeNO test. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

Then a series of further. Tests with a more elaborate, armatured machine connected to a digital screen. A spirometer. A machine implicated in histories of racialized calibration of the capacities and volumes of bodies.26 A machine of whose hidden inheritances you are aware as you are told how it works. The spirometer measures various things:

Slow vital lung capacity (VC). Or, how much air you can exhale in a gentle sigh until your lungs are empty.

Forced, expiratory volume (FEV). Or, how much air you can exhale rapidly, as fast as you can, in a second.

Forced vital capacity (FVC). The volume of air you can exhale in one continuous breath after a deep breath.

The technician guides you through each of these tests with animated gestural instructions. They help, but also amplify a sense of breathing as performance or work. Some of your efforts are better than others. Sometimes you get it right on the first try. Sometimes not.

A lung function test with a spirometer amplifies the sense of breathing as performance and as work. It is doubly interactive because the rhythms of inhalation and exhalation are traced via lines on a digital display that you watch as you breathe. The breather is asked to influence the speed, direction, and shape of the line. As the test begins you feel that your effort is influencing the line traced on the screen while the rhythm of the line remains beyond you. At one point you are asked to exhale absolutely everything, finding yourself watching that line going up and up until it starts to curve and then to flatten, hovering as you try to exhale every last molecule of air from your lungs, until finally, imperceptibly at first, the line begins to drop with the influx of air into your lungs.

The technician remarks on how unusually interested you seem in it all. You talk of a project at Modern Art Oxford in which you are involved.

***

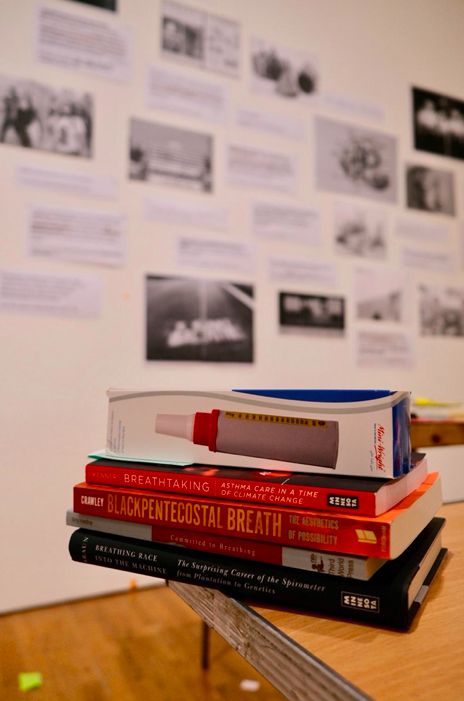

Installed as part of the Responsive Space exhibition at Modern Art Oxford (2 October 2020 - 18 April 2021), Breathing Worlds was the academic counterpart and accompaniment to the participatory arts project Breathworks. It was composed of quotations and images from research on breathing in the humanities and social sciences (Figure 2) that covered a seven-by-three meter wall-space. These materials had emerged initially from eight overarching but relatively open categories: breathing is..., breathing experience, breathing health, breathing environment, breathing politics, breathing violence, breathing technology, and breathing art. The idea was not to determine what breathing worlds are, but to create a compositional arrangement from which worlds, as modest pockets of spacetime, might emerge.27 The composition on the wall was complemented by a vitrine display in the entrance to the gallery. Here we gathered images, objects, and texts (Figure 3), the latter including:

● Lundy Braun’s Breathing Race into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Plantation to Genetics (2014)

● Ashon T. Crawley’s Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (2016)

● Alison Kenner’s Breathtaking: Asthma Care in a Time of Climate Change (2018)

● Tony Medina’s Committed to Breathing (2004)

In addition, an online event of the same name was organized and included contributions from ourselves, Alice Sharp (artistic director of Invisible Dust) and Patsy Isles (yoga instructor, activist, and Wellbeing associate at Words of Colour).

Figure 2. Video montage of Breathworks (foreground) with Breathing Worlds research (background). Credit: Modern Art Oxford.

Figure 4. Maquette of Breathing Worlds research display (1:10). Credit: Derek McCormack.

Figure 3. Close-up of objects destined for the vitrine display. Credit: Derek McCormack.

To plan the compositional arrangement of the research display inside the gallery, we worked with a scaled down (1:10) maquette featuring cut-outs of the print media made by Lucy (Figure 4). This miniature version became a tactile interface for experimenting with alternate compositions. And through this repositioning of ideas as relational objects, we realized that research outputs from each area, or each possible breathing world, resonated with ideas in many other fields — such is the uncontainable nature of breath.28 As such, the composition of Breathing Worlds became an exercise in Kristevan intertextuality (Julia Kristeva’s mediatic development of Bakhtin’s spatialization of literary language) that situates texts within open systems of distributed and emergent meaning-making.29 But we also understood intertextuality in a material, embodied way that paralleled the interstitial anatomy of the respiratory system. We drew parallels here with the para-structural materiality of the intercostal muscle tissues, which insert into, slip under, stretch across and knit between bones to give supple mobility to the ribcage.

In the end, Breathing Worlds was molecular and diffuse. On the research wall in particular, whitespace between each “p/article” meant a resemblance to debris in suspension. There were two reasons for this nebulous composition. The first was conceptual and aesthetic: visitors to the gallery would, to some extent, be able to make their own intertextual network of connections between the mixture of floating perspectives on breathing, rather than having the relations spelled out in a more determined way. We hoped to offer little envelopes of breathing space in which visitors could linger, even briefly, when working through the chorus of image and text.

Figure 5. Side view of Breathing Worlds research display. Credit: Modern Art Oxford.

Thinking about the possibility of these little envelopes was doubly important for a second reason. Like many places across the UK, the gallery was between closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic and directors were keen that the public should flow efficiently through the building while maintaining social distancing. That is, an additional task to the standard procedures of managing the gallery’s atmosphere and configuration of media

30

resided in controlling the mobilities of the breathing bodies of visitors. Our designs were consequently subject to examination beyond the usual curatorial concerns. Sparseness was a necessity. It felt poignant, if a little dystopian, that an exhibit about breath should be designed to reinforce divisions of literal breathing spaces due to the fear of airborne transmission. This fact was amplified further, of course, by how the visitor experience of Breathing Worlds at Modern Art Oxford, like almost everywhere else, was mediated by another interface — the mask. While Breathing Worlds did not engage directly with the politics of the mask, it nevertheless offered visitors opportunities to defamiliarize this increasingly ubiquitous interface, foregrounding its presence in the modification of everyday experiences of inhalation and exhalation (Figure 5).

***

26th April, 2021. A cardiac stress test. The John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. In anticipation, you remember your first single authored paper — about fitness machines, cyborg combinations of flesh and technology.31 You realise, with some surprise, that you have never been on a treadmill before. Your efforts are measured by 11 electrical sensors, each of which traces a line on a screen and an accompanying print-out on reams of paper. As your pace picks up and the incline changes you watch the lines on the screen, your breathing becoming more strained, sucking in the air through the mask, until eventually the technician tells you that you can take it off. You ask for the print-out but the technician declines. Like most tests it tells you little you did not already know, leaving you wondering about how something so palpable can fall so far below the threshold of so much attention.

Exhalation

Whether through death or through the persistence of degrees of diminished capacities, the COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to foreground breathing as a process of atmospheric transmission and circulation. It is highlighting the difficulties and inequities of partaking in un/common spaces of inhalation and exhalation. And it is focusing attention on everyday struggles around the question of exposure to elemental milieu and the forms of envelopment that limit such exposure. In this context thinking about breathing worlds has become even more important.32 Breathing worlds as both noun and verb. As worlds that breathe. Worlds that were breathed into being by others.33 These worlds are the backgrounds that are foregrounded, only sometimes intentionally, at every inhalation and exhalation. This foregrounding can be intentional, deliberate, controlled — as in various practices in which breathing becomes a mode of focused attention or attunement — or it can provide the basis of pneumatic forms of bodily discipline.34 But it can also be unwilled, unwelcome, and violent, as it is when worlds constrict, exhaust, asphyxiate, choke. Breathing worlds are always multiple. They are “textured and tangible and sometimes ephemeral.”35

Insofar as it refers to a process, the concept of breathing worlds signals also the labor of breathing, labor that is simultaneously individual and collective. The labor of breathing is the effort to inhale and exhale when neither can be left to their own devices. The labor of breathing involves turning attention to breath even when this attention often offers little more than a reminder of the feeling of bodily susceptibility. And the labor of breathing can be extended to the project of making visible or palpable or contestable the changing conditions in which breathing takes place. And as our collaboration, however modest, perhaps reminds us, the labor of breathing can animate shared attachments to the project of keeping open these little pockets of envelopment and exposure we call breathing worlds.

❃ ❃ ❃

Derek McCormack is a Professor of Cultural Geography at the University of Oxford. His current writing focuses on atmospheres and the elements. He is the author of Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces (2013) and Atmospheric Things: On the Allure of Elemental Envelopment, both published by Duke University Press.

Lucy Sabin is an artist-researcher whose work explores the interplay between media and environments, with a particular focus on themes of atmospheres and breathing. Her emerging practice has been featured by BBC Radio 4 and BBC Arts. Lucy has also been selected by Arts Council England as an awardee of Developing Your Creative Practice. Drawing upon an MRes in Communication Design from the Royal College of Art, Lucy is undertaking doctoral research in the UCL Department of Geography with support from the London Arts and Humanities Partnership.

- Alison Kenner. Breathtaking: Asthma care in a time of climate change (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

- See Ruha Benjamin, “Catching Our Breath: Critical Race STS and the Carceral Imagination,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 2 (2016): 145-156; Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- See Timothy Choy, “Distribution,” Society for Cultural Anthropology (2016); Paul Gilroy and Achille Mbembe, “SPRC in conversation with Achille Mbembe,” SPRC Podcast (2020).

- Sabin, 2020.

- See Felicity Callard and Elisa Perego, “How and why patients made Long Covid,” Social Science and Medicine (2021).

- Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

- Caylee Hong invokes a “user/breather” in her political design research. See Caylee Hong "Visualize-ing air: Data, icons, and translations of smog in Lahore," Society for Cultural Anthropology (2020).

- Kathleen Stewart, “Atmospheric Attunements,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29, no. 3 (2011): 445-453. 452.

- See Timothy Choy, Ecologies of Comparison: An Ethnography of Endangerment in Hong Kong (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Jane Macnaughton, “Making Breath Visible: Reflections on Relations between Bodies, Breath and World in the Critical Medical Humanities,” Body & Society 26, no. 2: 30-34.

- Choy, Ecologies of Comparison. My emphasis.

- Achille Mbembe, “The Universal Right to Breathe,” translated by Carolyn Shread, Critical Inquiry 47, no. S2. See also Gilroy and Mbembe, “In Conversation.”

- ”Participatory Arts,” Participedia (2018).

- See Ashton Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017); Sarah Jane Cervenak, “’Black Night is Falling’: The ‘Airy Poetics’ of Some Performance,” TDR: The Drama Review 62, no. 1 (2018): 166-169; John Durham Peters, “The Media of Breathing,” in Atmospheres of Breathing, edited by L. Škof and P. Berndtson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018).

- Regarding Covid-19, see Benjamin, “Catching our Breath”; Kristen Simmons, “Settler Atmospherics,” Society for Cultural Anthropology (2017). Regarding intersectionality, see LaToya Eaves and Karen Falconer Al-Hindi, “Intersectional Geographies and COVID-19,” Dialogues in Human Geography 10, no. 2: 132-136; Brett Bowman, “On the Biopolitics of Breathing: Race, Protests, and State Violence under the Global Threat of COVID-19,” South African Journal of Psychology 50, no. 3: 312-315; Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6: 1241-1299.

- Tim Ingold, “On Breath and Breathing: A Concluding Comment,” Body & Society 26, no. 2 (2020): 158-167.

- Follow this link for more information.

- Lucy Sabin, “Following Breathing,” The Polyphony (2021).

- Macnaughton, “Making Breath Visible.”

- Maxwell (1831-1879) quoted in Branden Hookway, Interface (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014), 66.

- See Johanna Drucker, “Reading Interface,” PMLA 128, no. 1 (2013): 213-220; Hookway, Interface.

- Andy Clark and David Chalmers, “The Extended Mind,” Analysis 58, no. 1 (1998): 7-19.

- James Ash, Interface Envelope: Gaming, Technology, Power (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- See Tim Ingold, “Footprints through the Weather-World: Walking, Breathing, Knowing,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute,” 16 (2010).

- See Melody Jue, Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020). Also see Engelmann on surfaces: Sasha Engelmann, “Towards a Poetics of Air: Sequencing and Surfacing Breath,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 40, no. 3 (2015): 430-444.

- See Peter Sloterdijk, “Airquakes,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27 (2009): 41-57; Lundy Braun, Breathing Race into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Plantation to Genetics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Peters, “The Media of Breathing”; Alison Kenner, Aftab Mirzaei, and Christy Spackman, “Breathing in the Anthropocene: Thinking through Scale with Containment Technologies,” Cultural Studies Review 25, no. 2 (2019): 153-171.

- Braun, Breathing Race into the Machine.

- Stewart, “Atmospheric Attunements.”

- See Luce Irigaray, Entre Orient et Occident: De la Singularité à la Communauté (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1999), 106; Ingold, “On Breath and Breathing.”

- Julia Kristeva, “Word, dialogue and Novel,” in Desire and Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, edited by L.S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University, 1980).

- Mark Dorrian, “Museum Atmospheres: Notes on Aura, Distance and Affect,” The Journal of Architecture 19, no. 2 (2014): 187-201.

- Derek McCormack, “Home-Body-Shopping: Reconfiguring Geographies of Fitness,” Gender, Place, and Culture 6, no. 2 (1999): 155-177.

- See Sasha Engelmann and Derek McCormack, “Elemental worlds: Specificities, exposures, alchemies,” Progress in Human Geography (2021).

- Natasha Myers, “How to Grow Liveable Worlds: Ten (Not-So-Easy) Steps for Life in the Planthroposcene” (2021).

- José de Abreu, The Charismatic Gymnasium: Breath, Media , and Religious Revivalism in Contemporary Brazil (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

- Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath, 29.

Suggested Reading