preface

Senses in the Air

Charles Keiffer

Volume Two, Issue Two, “Senses,” Introductory Essay

Are sensations contagious? Are they political? Can they be harnessed to motivate political action? Or are they outside of politics, outside of language, an unruly and unpredictable feature of sentience that we by turns put up with and enjoy? The authors and artists in this issue of Venti tangle with these questions from a variety of disciplinary and personal perspectives, many describing extraordinary and highly specific measures taken to harness the senses. In this sensory work, they also point us to a sense of a shared experience that otherwise remains stubbornly beyond the writer’s grasp.

In 1907, the German sociologist Georg Simmel noted that to study culture solely through “those large objectivized structures that constitute the traditional objects of social science” — the law, political regimes, ideologies — would be wholly inefficient.1 “That we get involved in interactions at all,” Simmel wrote, “depends on the fact that we have a sensory effect upon one another.”2 This shared sentience and the exchanges that it yields are the central elements of social and cultural order.

The medium that carries these senses is, of course, the air. Decades after Simmel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty would call the body “the possibility of situations,” but this is already a body in air.3 While past issues of Venti have considered how air mediates aesthetic experience, in “Senses,” air moves beyond the role of a mediator to become an active agent delivering experience onto hopelessly receptive bodies who receive sensations, and then thoughts, that we did not ask for and sometimes did not want.

Among those influenced by phenomenology, it is taken for granted that sensing precedes feeling, thinking, or knowing. We know the world through our senses. As the world changes, however, what can be sensed, and what can be thought and known, changes as well. The aim of this issue is to expand readings of the body as a site of sensory appreciation to consider the air as a carrier of sensations. If sensing precedes knowing, then air, the body’s environment, must certainly precede sensing. The senses are rich with possibilities.

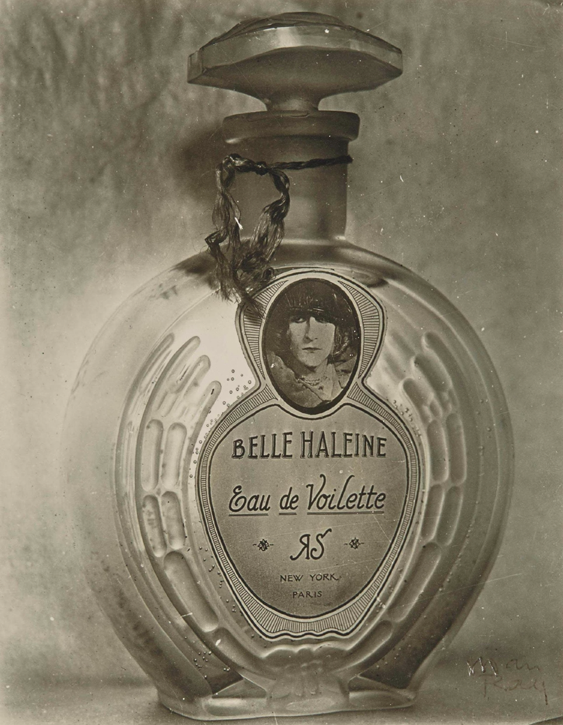

Fig. 1: Marcel Duchamp (Rrose Selavy), Man Ray, Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, 1920-21.

Of the supposed five, the sense that illustrates the air’s agentive qualities most clearly is smell, which many of the essays within engage. Of course, we are now painfully aware of the airborne threats coming into our noses. But the field of “Olfactory art” is nothing new, as Madalina Diaconu traces in her essay, “The Stylistics of Olfactory Art as an Idiolect of the Atmosphere.” Its most obvious beginning is in Marcel Duchamp’s 1938 Surrealist Exhibition in Paris, where the aroma of roasted coffee was included in the immersive installation to evoke “the perfumes of Brazil.” Even years prior, it could be argued, Duchamp explored scent in his 1921 “assisted readymade,” Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath, Veil Water) (fig. 1), where the label on a Rigaud brand perfume bottle was altered to feature an image of the artist’s female alter ego, Rrose Selavy, and to display the title of the work. While the bottle was empty, the choice of object itself and the appearance of Selavy suggests an acknowledgement of the connection between scent and gender, and the ways the visual, as in perfume marketing, and the olfactory inflect one another.

It may feel like smell is having another moment.4 Anicka Yi’s 2021 installation, In Love with the World, in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall featured a “scentscape,” where her airborne robots emitted changing odors inspired by the history of the surrounding London. These included burning coal reminiscent of the industrial revolution and spices that were believed in the fourteenth-century to protect the eater from the black death. But how scent travels in the air, and whether our bodies detect it, is a force beyond any artist’s control. Naomi Rea, in Artnet News, wrote that, “these confusing scents are not straightforward; they ask you to heighten your awareness, and breathe deeply”5 while other critics noted disappointment at being unable to smell anything at all. Laura Cumming, in The Guardian, called the scentscape “so imperceptible as to be wholly unsuccessful,”6 while Anna Souter in Hyperallergic wrote that “the absence of the promised ‘scentscapes’ is surprising.”7

Some of the thinkers in this issue might encourage these critics to reconsider whether the imperceptibility of the scents in In Love with the World is in fact a failure or a feature, prompting us to consider how our experience of scent is always mediated by our expectations. In his essay, “Shimmering Cloud: Psychoanalytic Notes on the Perfumer’s Note List,” Matt Morris meditates on the impossible task of describing scents. This is more than a poststructuralist critique of language and meaning — the “fragrance notes” on a perfume’s packaging that describe each scent rarely if ever refer to the actual ingredients used, making them less a description of a particular packaged scent than an evocation of a certain mood, or fantasy. Things smell, or they don’t, because of what oils or particles they emit into the air, but, as in Duchamp’s Belle Haleine, when we talk about fragrance, we are also talking about fantasy and desire. That fragrances are thought to smell “feminine” (floral, fruity, sweet) or “masculine” (woodsy, musky, and often, “leathery”) reveals the degree to which gender itself is, like a scent profile, a fantasy discursively upheld.

Shivani Kapoor’s “‘The Air Smells Rotten’: Caste and Senses in and around a Tannery” also explores the role of smell in upholding social order. Kapoor’s case study is the leather tanneries in Uttar Pradesh, India, where the smell of the tannery that lingers on the bodies and clothes of the leatherworkers signals their status, functioning in service of the caste system. In communities around a leather tannery, social mixing is determined by a person’s smell — or, rather, how others perceive their smell.

Hsuan L. Hsu might add that in the United States of America, the situation is hardly different. Hsu’s article, “Colonial and Anti-Black Legacies of Fragrance and Deodorization,” explores the racialization of bodily odors through deodorant campaigns, showing that smelling “clean” has also always been smelling white. As he quotes the poet William Nu’utupu Giles, “Was a slave this nation’s first anti-perspirant? / just something you bought to make you sweat less?”

Indeed, the transatlantic slave trade had many important olfactory elements: Olaudah Equiano described the unbearable stench on board the slave ship that brought him to the Americas in the eighteenth century as “such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life,”8 while, as M. Nicole Horsley notes in her article, there are also claims that the ships carrying captive Africans could be smelled from afar as they neared land. Érika Wicky’s “Navigating by Smell: On Scent, the Sea and Distance” dives (or sails) into this olfactory interplay between land and sea in the colonial era. Windborne odors, Wicky shows, are crucial to understanding the experiences of sailors, from their navigational abilities to their emotional lives.

From the beginning of European colonization, people on all sides were exposed to smells entirely new which they interpreted through old beliefs and ideas about the world. Andrew Kettler traces the history of smells functioning in the service of violence in the colonial era. His essay, “The Miasmic Theft of Modernity: Sulfuric Aromata and Early Modern Empires,” considers how Iberian and Western European colonizers in the Age of Exploration interpreted the smells in the so-called “New World,” West Africa and South Asia through their belief that sulfuric odors signified evil or demonic activity. This preconditioned belief in the moral significance of smells, Kettler argues, gave colonists a sort of divine authority to “sanitize” areas where sulfuric odors were detected, which tend to also be areas rich in mineral nutrients.

We are never in control of what the air may be carrying in our direction next. As Tonino Griffero put it in an earlier issue of Venti, “the wind blows where it wishes.” To sense is already to react, because what thoughts or desires a sensation may trigger occurs before we have had time to consider. This is where it gets political, as anyone’s inventory of thoughts and desires is culturally limited. The smell or taste of unfamiliar foods or bodies can evoke disgust or curiosity and do it simultaneously. When we attempt to control how we react, we decide what feelings to name and what to ignore.

Other essays in this issue ask how else the senses might be made to function in the service of something outside of white supremacy or global capitalism, from black joy to environmental awareness and empathy. With examples ranging from the middle passage to mukbang, M. Nicole Horsley explores how the black body senses in ways that have not yet been articulated under white supremacy, deploying parentheses and italics where the existing language is especially limited. Her analysis moves from the nose through the mouth and into the throat, highly sensitive areas that she shows to be not only uniquely racialized but also uniquely underappreciated sites of radical pleasure.

Like smell, the other senses are also interpreted through expectation and belief. Emily Leifer and Desiree Foerster both consider how space might challenge these beliefs by reorienting our sense of being in a body around other bodies. Spaces such as James Turrell’s early sensory deprivation chambers for Leifer or Philippe Rahm’s installations for Foerster represent ways that architecture can get around the hyperobject, too-big-to-sense, qualities of climate change to make them resonate on the level of individual bodies.

Dancer and scholar Raffaele Rufo also aims to make environmental awareness something we feel in our bodies. Motivated by readings in ecology and phenomenology, Ruffo describes a process he undertook while under lockdown in his hometown outside Milan. Every morning and afternoon, he would go into the forest on the outskirts of his town and explore the possibilities typically foreclosed to an urban-dwelling body — rolling in the dirt and touching trees with his bare hands until he began to grasp the extent to which his senses were already deeply entangled with the earth. But this is not your typical “man escapes into nature” narrative — Rufo does not pretend to be deep in a primeval forest or anything other than a person in a public park outside Milan, and this is precisely the point. The background sounds of cars and motorcycles were part of his sensory experience of nature, including the sense of self-consciousness, and it was from this footing and not in spite of it that he established communion with trees, literally embodying the long-held understanding in ecological thought that humans do not “cross into” nature, but always already inhabit what Donna Haraway has termed “naturecultures.” Like Turrell, Rahm, and Yi, Rufo aims to resensitize us to the urgent needs of the nonhuman world around us by emphasizing the “sense” in the term.

In 1966, Michel Foucault described in The Order of Things how during the enlightenment the ocular or visible was privileged above all other modes of knowledge, opening all that could not be learned through sight to suspicion. Since then, the humanities have slowly begun to seriously consider this claim and the trauma that this ocular-centrism has inflicted on nonhuman worlds. Scholarship in this vein has been steadily increasing since, but slowly. This is in part because the disciplinary divides within the humanities are themselves products of enlightenment thinking, and no one field is best equipped to handle so broad a topic, especially when what counts as “scholarship” is still limited to the ocular tradition of words on a page. We of course are not immune, or even strongly opposed, to this tradition, but as a mainly online journal, we take advantage of the opportunity to include different kinds of media in our issues. This issue of Venti includes contributions from visual artists, olfactory artists, dancers, and professors and students of Media Studies, Art History, Architectural History, Philosophy, and English, a multidisciplinary and multisensory roster befitting so slippery a topic as “the senses.”

❃❃❃

Charles Keiffer is the managing editor of Venti Journal.

- Georg Simmel, “The Sociology of the Senses,” in Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings, ed. David Frisby and Mike Featherstone, Theory, Culture & Society (London, UK: Sage Publications, 1997), 110.

- Simmel, 110.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London; New York: Routledge, 1962), 392.

- Anna North, “My Year of Smells: The Power of Perfume in a Plague Year,” Vox, December 11, 2021, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22783776/long-covid-loss-of-smell-taste.

- Naomi Rea, “‘You Have to Experience It in the Radical Present’: How Anicka Yi’s Ultra-Sensorial Tate Commission Resists the Age of Instagram Art,” Artnet News, October 13, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/anicka-yi-turbine-hall-commission-2019839.

- Laura Cumming, “Anicka Yi’s Turbine Hall,” The Guardian, October 17, 2021.

- Anna Souter, “At Tate Modern, an Installation Blurs the Line Between Technology and Biology,” Hyperallergic, November 16, 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/686905/at-tate-modern-an-installation-blurs-the-line-between-technology-and-biology/.

- Olauah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; Or Gustavus Vassa, the African (W. Cock, 1815), 52.