A Soft, Sympathetic Touch

Walt Whitman and the Eroticism of Wind

Wesley Cornwell

“Touching upon draws the other close through the intimacy of breath while still respecting the other’s irreducible dividuality. Through breath, dividuals can experience intimacy both within and between themselves.”

Volume Two, Issue Three “Wind,” Essay

Treasures lie within a 1913 edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass — not only the poems of the American bard but also the twenty-four colored plates by English artist Margaret C. Cook. The plate here presented, “Living beings, identities now doubtless near us in the air that we know not of,” depicts a nude young man standing in community with the natural world around him. He leans against a tree, contemplative, arms crossed as he gazes in the direction of a breezy figure standing beside him. The wind, erotic and tangible, is the primary focus here as it is in Wesley Cornwell’s text, where the subjective meets the material in an expanded corporeality that brings us all into the collective, Whitmanian kosmos.

“A synaptic exchange resides in the same event space of a poem in the course of being written, of a breeze” — Emanuele Coccia, Life of Plants1

Wait

I might not tell everybody, but I will tell you (1, 40).2

Each evening, as the sun slips towards the horizon, I leave the cool air-conditioning of my Airbnb and walk to the nearby Cascadilla Gorge. I follow the stone path, which snakes alongside the creek and slowly climbs towards Cornell’s campus. As I approach the first waterfall, the water’s quiet babbling crescendos to a roar, temporarily drowning out the world’s anxious hum. Halfway along the trail, I pause to sit and watch the creek rush by. The water’s steady cadence is accented by the bright arpeggios of birds and the rustling of leaves in the wind. I do nothing but listen, / To accrue what I hear into this song, to let sounds contribute toward it (1, 36).

Margaret C. Cook, “I do not know what it is except that it is grand, and that it is happiness” illustrated in Walt Whitman, Poems from Leaves of Grass (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1913), 132.

Along these walks, I’ve found myself returning to the work of Walt Whitman, the great American poet of cosmic relationality. I am both pulled towards and skeptical of his unyielding belief in the potential of poetry to engender more egalitarian, democratic relationships. Despite my many reservations, at a moment when outrage, antagonism, and polarization dominate both the political and personal, Whitman’s ecstatic embrace of connection feels like a lifeline, a testimony to the power of other ways of relating to others.3 My attention to Whitman’s poetry as a salient alternative to the oppositional frictions that characterize contemporary American politics is largely inspired by Jane Bennet’s Influx and Efflux: Writing Up with Walt Whitman. In this beautifully sinuous book, Bennett reorients her interest from material vibrancies (the focus of her previous book4) to airy, apersonal influences as theorized vis-à-vis Whitman’s poetry. In fact, she renders the book’s primary focus in atmospheric terms: “it is sympathy as a more-than-human atmospheric force that greatly interested Whitman.”5 And, I’ll add, it is precisely sympathy’s atmospheric qualities that also interest Bennett.

Bennett’s ethereal theorizing is notable both because of a recent interest in air and atmosphere in media theory, art history, and aesthetic philosophy6 and because the literary tradition of American nature writing is — more often than not — earth-bound, a grounded-ness that can be characterized as “an earthy curiosity for the erotic vitality of life.”7 Bennett’s atmospheric theory of relationality draws attention to the diffused, apersonal circulation of energy in Whitman’s poetry; in doing so, she makes a compelling argument for understanding sympathy as an “atmospherics of indeterminate eros.”8 Yet, she foregoes a sustained engagement with the role of air, wind, and breath themselves in Whitman’s corpus. The atmospheric guides Bennett’s thought principally as a metaphor, and she devotes little attention to the erotic, affective potential of the atmosphere-as-such, that is as the common air that bathes the globe (1, 22).9

So then, my wager is that attending to Whitmanian wind will engender a greater understanding of how air itself can be felt as erotic. This essay is guided by three intertwined questions: first, through an atmospheric curiosity, what can we learn about the erotic touch of wind as air-in-motion? Second, how might this sympathetic hapticity arouse an expanded sense of self? Third, in what ways is this apersonal, atmospheric sensuality decidedly — although perhaps not exclusively — queer?10 In exploring these questions, I proceed less by a logic of argumentation and more through an experiment in worlding,11 which attempts to render sensible the “paradox of personal endeavoring in a world of pervasive influence.”12 Said differently, through this essay, I search for one possible way to re-tune the hazy edges of perception through attention to the hapticity of air. My words itch at your ears till you understand them (1, 77).

Move

Urge and urge and urge / Always the procreant urge of the world (1, 3).

Before turning to Whitman, I want to briefly map the unstable relationship between air and wind and, more specifically, the eroticism of air becoming wind. To that end, the Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius serves as a helpful guide for theorizing how air-in-motion becomes both sensual and sensuous.13 Lucretius begins De rerum natura (On the Nature of the Things) with a prayer to Venus, whose life-giving power indebts every living creature — including, of course, Lucretius — to her. He praises how “the door to spring is flung open and Favonius’ fertilizing breeze, released from imprisonment, is active.”14 The welcome presence of Favonius, god of the West Wind, does not merely signal the return (and rebirth) of spring: his fertilizing breeze carries life itself. At first, Lucretius’s invocation would seem to be fairly banal: anyone with spring allergies is all-too-aware that the wind carries pollen. We might reasonably understand Favonius to be merely a vector for reproduction, carrying new life among and between plants yet not intrinsically fertile/fertilizing himself. The earth grows seed for freedom, in its turn to bear seed, / Which the winds carry afar and re-sow, and the rains and the snows nourish (1, 146).

Yet, this interpretation misunderstands Lucretius’s conception of wind: he writes that “air […] becomes wind when it is agitated.”15 The wind in De rerum natura is, in turn, violent, capricious, and impetuous; however, Lucretius’s use of the word “agitated” draws particular attention to the arousing, stimulating, exciting force of wind.16 If I worship one thing more than another it shall be the spread of my own body, or any part of it. […] Winds whose soft-tickling genitals rub against me it shall be you! (1, 33). Favonius’s breeze is not only a signal of or vector for fertility but also a stirring, stimulating force itself. Said differently, the wind’s force is not limited to procreation; rather, it allows for an experience of the erotic beyond mere sexual contact. Instead, the erotic is expanded to encompass the experience of affective and physical connection to the world.17 The agitated movement of air renders it agentive, which returns us to the sympathetic force of Whitmanian wind.

Attest

The curious sympathy one feels when feeling with the hand the naked meat of the body, / The circling rivers the breath, and breathing it in and out (1, 132).

As I suggested in the introduction, Bennett centers sympathy in both her reading of Whitman and her theorization of the affective relays between external influences and internal states. Importantly, sympathy is far more theoretically specific than a feeling of pity or commiseration for others. In a 2014 essay on Whitman, Bennett describes sympathy as “an impersonal ontological infrastructure, an undesigned system of affinities.”18 Yet, in Influx and Efflux, she repeatedly describes sympathy as an “atmospheric current,” a decidedly less rigid and ordered flow of affinity than her earlier language of “infrastructure” might have suggested.19 As this essay shows, the loosening of Bennett’s metaphor is more consistent with Whitman’s own airy formulation of sympathy than her earlier, more structured theorization. For Bennett, sympathy is not an internal emotion but rather an apersonal communicative flow, an agentive flux that does not presuppose intentionality and is not bound to or limited by human action.

Furthermore, although Whitman’s and Bennett’s works allow for creative access to and intellectual understanding of sympathy, I want to stress that it is neither poetic license nor a theoretical tool; rather, it names an apersonal, affective current that is principally phenomenal,20 not artistic or conceptual. Consider, for instance, when Whitman writes I am he that aches with amorous love; / Does the earth gravitate? does not all matter, aching, attract all matter? / So the body of me to all I meet or know (2, 363). Whitman’s rhetorical question illuminates the apersonal nature of sympathy, which is — like gravity — an impartial attraction intrinsic to the world (spacetimematter21) itself.

Despite the impartiality of sympathy (and related attractions, pressures, and forces), we nevertheless experience it as personal. Sympathy flows unto us, we are rightly charged (1, 231). This affective spark is felt as the shuddering longing ache of contact (1, 232). So then, how does wind engender an erotic, aching experience of sympathy with/in/of the world? In turn, how does this sensual contact reshape, soften, caress the boundaries between the self and the world? With these questions in mind, I now turn to three types of sympathetic touch, three ways that the wind in Whitman’s poetry makes sympathy sensible: dilating, rubbing, distilling.22 I am he attesting sympathy (1, 28).

Dilate

Wider and wider they spread, expanding, always expanding (1, 73).

As Matt Miller demonstrates in Collage of Myself: Walt Whitman and the Making of Leaves of Grass, Whitman was “intensely” preoccupied with the word dilation, which names a process of enlargement to incorporate the world within oneself.23 Bennett folds dilation into a larger set of Whitmanian dispositions as a “presumptive friendliness” and “effusive affability.”24 Although Miller traces the particular nuances of dilation in Whitman’s writings and Bennett develops it in the broader context of Whitman’s theory of self, neither sufficiently considers — or really even acknowledges — the central relationship between porosity, breath, and pleasure within the experience of dilation.25

In the Preface to the 1855 version of Leaves of Grass, Whitman writes that the “greatest poet hardly knows pettiness or triviality. If he breathes into anything that was before thought small, it dilates with the grandeur and life of the universe.”26 By linking dilation to breath, Whitman underscores how the circulation of air into and through the lungs changes one’s relationship to the air through widening and penetrating corporeal boundaries.27 In more concretely social terms, dilation describes a changed relationship between the poet and his readers. When Whitman writes I dilate you with tremendous breath, I buoy you up (1, 63), he describes the transfiguring effects of the exhalation of the I and the inhalation of the you. Through breath, the poet’s words transverse the porous boundaries of bodies so as to expand them. Still, Whitman’s buoying breath is contingent on the reader’s willingness to be buoyed.28 In other words, Whitman describes not a unidirectional flow of air but rather a mutual, willing exchange of breath.

Dilation is not exclusively metaphorical, conceptual, or poetic, nor is it limited to an ever-expanding concept of interconnection and relationality between the poet and you, thoughts, or even the universe. It can be a deeply pleasurable experience tied to specific moments of connection. For example, in describing the experience of riding a horse, Whitman writes his nostrils dilate as my heels embrace him, / His well-built limbs tremble with pleasure (1, 43). This moment is illustrative because it reinforces the relationship between dilation and breath (his nostrils dilate), touch (as my heels embrace him), and pleasure (His well-built limbs tremble with pleasure). As a type of sympathetic touch, dilation engenders an expanded yet specific experience of connection through the movement of air as breath.

Through these examples, I want to stress that dilation is not the dissolution of boundaries or the total evaporation of a distinction between inside and outside.29 As Bennett writes, “the phenomenology of sympathy pursued proceeds less by a logic of projection than of dilation — the opening wider of the pores of the body so as to receive more of the outside.”30 Dilation is best understood as the easing of exchange, the loosening of seams, the relaxing of membranes. It does not eliminate exteriority and interiority but rather names the condition of exteriority within interiority made possible through the body’s elasticity. Dilation is, in this way, a vulnerable experience: it is a mutually constituted receptivity, allowing oneself to be penetrated at the same time that one is made penetrable.31 This reciprocity underscores how the receptivity engendered through dilation can be understood as a kind of “social agency,” refusing more normative binaries of active/passive or subject/object.32 There is that in me — I do not know what it is — but I know it is in me (1, 81).

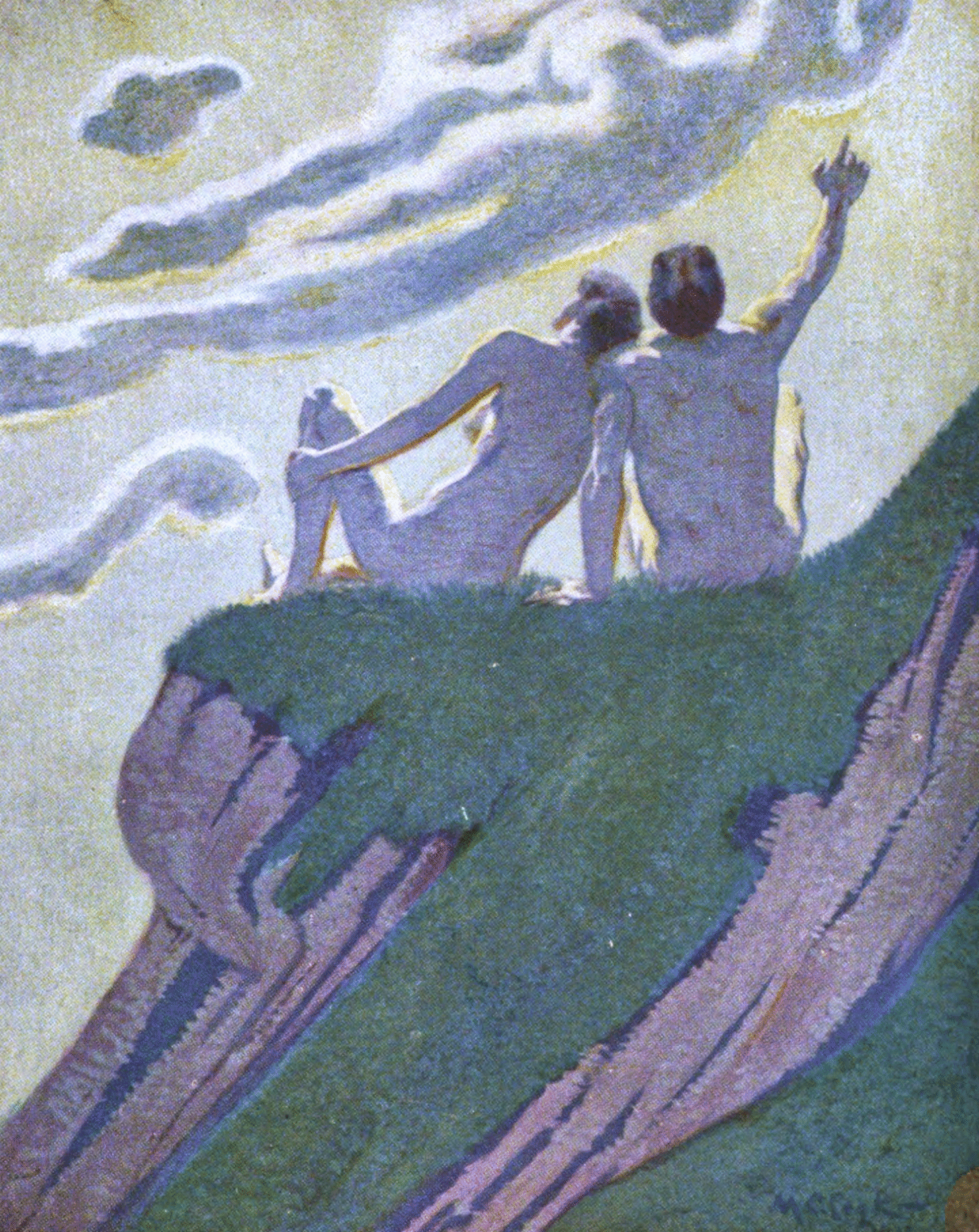

Margaret C. Cook, “Living beings, identities now doubtless near us in the air that we know not of” illustrated in Walt Whitman, Poems from Leaves of Grass (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1913), 10.)

Rub

This the touch of my lips to yours, this the murmur of yearning (1, 24).

The wind’s next type of sympathetic touch is to rub against the skin: if I worship one thing more than another it shall be the spread of my own body, or any part of it […] Winds whose soft-tickling genitals rub against me it shall be you! (1, 33). In this moment of expansive eroticism, Whitman temporarily teases apart two motions that are, in fact, simultaneous: first, the body spreads, compressing distance through its extension.33 While dilation makes sensible the porosity of the body’s boundaries, the body’s spread extends the boundary itself. However, in both cases, the boundary remains intact. Whitman’s worship is not a dissolution or disintegration but rather a reinscription of corporeal limits, which is felt through the wind’s second motion: rubbing. To rub is not to move between interior and exterior but rather to linger at/on the boundary. Touch is the recognition of the boundary, but more importantly, it is also the creation of one, allowing us to theorize sympathy in both descriptive and performative terms.34

By both spreading and rubbing the boundaries of the self, the wind’s tickle becomes erotic: “the wind causes all that it touches to quiver or stir, to be moved or convulsed.”35 The wind’s arousing effect has obvious resonances with Lucretius’s agitated and agitating air. Yet, for Whitman, the wind’s excitative caress engenders a changed subjectivity: Is this then a touch? quivering me to a new identity (1, 39). How can we make sense of Whitman’s suggestion that, through the wind’s touch, the self experiences itself to be extended and then made anew? The possibility that the wind’s gentle rub can tease us to a new, aroused identity is politically charged; it obligates us to consider forms of solidarity that may, at first, feel misaligned with the ways in which we have been habituated to understand our relationships with others.36

To puzzle through this experience of connectedness, I turn to queer theorist Leo Bersani, who proposes an “an ontological reality: all being moves toward, corresponds with itself outside of itself… the self out there is ‘mine’ without belonging to me.”37 For Bersani, this extension of self without possession is explicitly queer while still encompassing all types of sexual encounters. He unambiguously writes that “all love is, in a sense, homoerotic.”38 Paradoxically, sensual desire emerges from and is cultivated by embracing difference at the same time that we long for sameness. The wind renders this dual motion sensible by both changing the boundary between self and other and then heightening the awareness of that boundary through touch.

While my primary focus in this essay is how particular types of erotic sympathy are made phenomenal by the wind, the wind’s rub transcends human relationality, agency, or subjectivity. This impartiality is elucidated through Bersani’s notion of homoness, which “can first be experienced as a communication of forms, as a kind of universal solidarity not of identities but of positionings and configurations in space, a solidarity that ignores even the apparently most intractable identity-difference: between the human and the nonhuman.”39 For Bersani, this broad sense of connection is experienced as communication, which — despite the linguistic or (more generally) semiotic overtones — is not necessarily language-based. Rather, Bersani connects the experience of homoness to “positionings and configurations in space,” a sympathy and solidarity that necessarily comes from spatiotemporal proximity without being preconditioned on a notion of human agency. Long I was hugg' d close — long and long (1, 72).

Distill

Now on this spot I stand with my robust soul (1, 72).

The third and final type of the wind’s sympathetic touch is distillation. Near the beginning of "Song of Myself," Whitman writes, I breathe the fragrance of myself and know it and like it, / The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it (1, 2). At first, Whitman seems to be cautioning against the dangers of one’s own body. He goes on to contrast the inebriating effect of the body’s olfactory extension with the purified (and, presumably, purifying) air of the atmosphere: The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless, / It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it (1, 2).40 Whitman inhales his scent but stops before becoming intoxicated, turning instead to the tasteless, odorless air beyond himself. In his critical commentary, Ed Folsom offers an intuitive interpretation of this passage, writing that “Whitman breaks out of enclosures, whether they be physical enclosures or mental ones. […] They are all ‘intoxicating’ — alluring, to be sure, but also toxic. […] Whitman urges us to escape such enclosures, to open up the senses fully, and to breathe the undistilled atmosphere itself.”41 Folsom’s analysis echoes the earlier-discussed negotiation between interiority and exteriority, but now, this tension is shaded by liberatory overtones; Whitman urges us escape the familiar confines of ourselves to pursue a naked freedom out in the world. We ought to be pursuing pure, undistilled air.

And yet, this understanding of distillation is complicated by a later section of the poem in which Whitman extols, Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touch' d from, / The scent of these arm-pits aroma finer than prayer (1, 33). Whitman describes a haptic relay through which the corporeal becomes holy: the scent of the poet’s body is made divine while simultaneously the scent itself makes the poet’s body divine. This making-holy of the body is echoed in the poem “This Compost,” in which Whitman describes the cyclical exchange between life and death, the emergence of the new from the decomposition of the old. He writes that the nature distills such exquisite winds out of such infused fetor [from corpses] / It renews with such unwitting looks its prodigal, annual, sumptuous crops, / It gives such divine materials to men, and accepts such leavings from them at last (1, 213). Here, distillation is a resurrection; it is both a purifying transformation and an animating force.42 This agricultural renewal is reminiscent of Favonius’s fertilizing breeze, but Whitman stresses that we are entangled within this sublime43 cycle: while alive, we receive divine crops from nature, and in our deaths, nature receives us as divine. The cycle of life and death is also echoed in "Song of Myself" when Whitman writes of grass transpiring (literally “breathing forth”) from the breasts of young men (1, 7). Even in sites of death (graves), Whitman finds life: The smallest sprout shows there is really no death […] And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier (1, 8).

So then, distillation is a type of sympathetic touch that might, more accurately, be described as a temporally extended state change. It is not a corporeal widening or extension but rather the transcendence44 of the body’s boundaries only to reconstitute them through a broader sense of life itself. While dilating and rubbing are primarily experienced as reconfigurations of the body’s spatial limits, distilling exceeds and then remaps those limits in time. Distillation attenuates the body’s temporal limits through an extended notion of self not merely as defined by a particular material form but rather as constituted through the experience of matter itself as affectively charged. When Whitman writes I effuse my flesh in eddies (1, 82), he names the experience of distillation: gradually pouring oneself into swirling, purifying currents of energy.45 All goes onward and outward (1, 8).

Margaret C. Cook, “Whose happiest days were far away through fields, … he and another wandering” illustrated in Walt Whitman, Poems from Leaves of Grass (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1913), 81.

Touch

Human bodies are words, myriads of words (1, 266).

Having traced three types of the wind’s sens(ual/uous) touch, I now briefly turn to the challenge of writing up wind and articulating atmospheres. In Influx and Efflux, Bennett stretches the contours of language to “write up” a new grammar of dividuality.46 Her pursuit of an apersonal poetics “amplifies and elevates ethically whatever protogenerous potentials are already circulating.”47 Through her supple prose, she re-sensitizes the reader to the vibrancy of matter, making sympathies sensible.48 To this end, Bennett turns to the literary techniques through which Whitman writes up a model of self that acts without prioritizing “directness, drama, or overt might.”49 In particular, she lingers on Whitman’s use of middle-voiced verbs, which “bespeak of efforts proceeding from within an ongoing process.”50 Although the middle voice is nearly unthinkable in English, Bennett senses a middle-ness in Whitman’s use of verbs like to write up, to partake, to bespeak, to float, to animate to, to attest to, and to promulge.51 These verbs position the speaker as acting in the midst of a more broadly distributed field of agentive (which is not to say “intentional”) forces; “middle-voiced verbs do not presumptively bestow agentic priority upon the human beings in the mix, even as they acknowledge the weight of human efforts in tilting the trajectory of the assemblage.”52 To me the converging objects of the universe perpetually flow, / All are written to me, and I must get what the writing means (1, 25).

And yet, in the context of trying to understand the eroticism of wind (that is, air-in-motion), the question of writing is — despite the irony of this essay’s existence as prose — secondary to a more relevant question about the orality of words, that is the activation and expression of language through breath. For feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray, the relationship between speaking and breathing has become misbalanced and necessitates an urgent rethinking.53 For Irigaray, speech (exhalation, expulsion, efflux) has supplanted breath (the circulation of air through inhalation and exhalation, influx and efflux). By privileging speech, we have left ourselves breathless, wheezing and gasping for air. Whitman reminds us to forget not that Silence is also expressive (1, 156).

In response to this, Irigaray offers an erotic alternative: touching upon. Like Whitman’s use of middle-voiced verbs, touching upon “privileges verbs expressing dialogue, doing together; it uses to, between with, together.”54 However, Irigaray’s call for more liminal communication55 — which resists sharp distinctions between subject and object, between acting and being acted upon — is not only linguistic but also haptic. Like wind itself, touching upon is principally phenomenal: “in communicating, then, touching upon intervenes, a touching which respects the other proffering him/her attentiveness, including carnal attentiveness.”56 Touching upon draws the other close through the intimacy of breath57 while still respecting the other’s irreducible dividuality. Through breath, dividuals can experience intimacy both within and between themselves. Touching upon is a form of erotic relationality that preserves the specificity of the self while simultaneously reconstituting and being reconstituted by an embrace of the other. To touch my person to some one else's is about as much as I can stand (1, 38).

Spread

I swear I begin to see the meaning of these things (1, 205).

In the final section of “I Sing the Body Electric,” Whitman extols the curious sympathy one feels when feeling with the hand the naked meat of the body / The circling rivers the breath, and breathing it in and out (1, 132). My goal in this essay has been to render sensible the curious forms of sympathy engendered through the circulation of air, the eddies of wind that quiver the self into a broader experience of connection with and in the world. The dividual is dilated to external influences, rubbed to an expanded corporeality, distilled into an extended sense of being alive. The erotic touch of air-in-motion can engender a changed self, yet — as has been emphasized throughout this essay — these forms of sympathetic touch are a mutually constituted relationality, an experience of willing egalitarianism that is an effortful but not necessarily purposive practice. Through the wind’s touch, the self attunes and is attuned to atmospheric influences, which remain effectual even as they linger on the edge of perceptibility. The reciprocal exchange between self and world is contingent: it’s a risk to consciously experience oneself as susceptible to external influences.

Both through and alongside Bennett’s work, I’m pursuing a “mode of subjectivity and action, wherein the forces of nonhuman agencies and the ubiquity of stupendous, ethereal influences are acknowledged, become more felt, and, given more of their due, become slightly more susceptible to being inflected, for example, toward an egalitarian politics.”58 In fact, Whitman himself succinctly articulates the relationship between the erotic and the egalitarian, writing that his “verse strains its every nerve to arouse, brace, dilate, excite to the love & realization of health, friendship, perfection, freedom, and amplitude. There are other objects, but these are the main ones.”59 Through this essay, I join Whitman in his endeavor, straining against the expressive limits of language and attending to the motion of air as one way through which we can feel ourselves pulling and being pulled towards more democratic forms of sociality. Now I see the secret of the making of the best persons, / It is to grow in the open air (1, 229).

This growth is a slow, uncertain process; the realization of self in relationship to others is a labor of patience, faith, and love. On Whitman’s encouragement, I witness and wait (1, 5).

Acknowledge

In a letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Whitman implores, “Answer me by next mail, for I am waiting here like ship waiting for the welcome breath of the wind.”60 In writing this essay, the wind in my sails has been—to name only a few friends and colleagues—Stacey Berman, Caroline Hertz, Eesha Kumar, Daniel Large, Olivia Stowell, Tarushi Sonthalia, Erin Valentine, and the editors and reviewers from Venti. And, of course, John. I have perceiv'd that to be with those I like is enough (1, 124).

❃ ❃ ❃

Bio

Wesley is a cultural theorist and theater designer, currently pursuing a PhD in Theatre and Performance at Columbia University. His work attends to the bodily impact of ordinary affects, the chronotopic histories of queerness, and the mutually-constitutive relay between sensation, subjectivity, and sociality. His related interested include phenomenology, eco-criticism, and the techno-cultural history of light. He holds a Master in Design Studies from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and a B.A. in Anthropology and Theater from Princeton University. Website: wfcornwell.com

- Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, translated by Dylan J. Montanari (Medford, MA: Polity, 2019), 116.

- Unless otherwise noted, quotes from Whitman’s writings come from Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass: A Textual Variorum of the Printed Poems, ed. Sculley Bradley et al., The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman (New York, N.Y.: New York University Press, 1980). The parenthetical following each quote will note the volume and page number.

- In particular, I’m troubled by Whitman’s emphasis on American exceptionalism, his faith in capitalism, and his views about race. For more on these complexities, see including Cristin Ellis, Antebellum Posthuman Race and Materiality in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Baltimore, Maryland: Project Muse, 2018); Andrew Lawson, Walt Whitman & the Class Struggle, Iowa Whitman Series (Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2006); Carolyn Sorisio, Fleshing out America: Race, Gender, and the Politics of the Body in American Literature, 1833-1879 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002).

- Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

- Jane Bennett, Influx and Efflux: Writing up with Walt Whitman (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 27.

- For only a few examples, see Giuliana Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022); Steven Connor, The Matter of Air: Science and the Art of the Ethereal (London: Reaktion Books, 2010); Tonino Griffero, Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014.; Derek P. McCormack, Atmospheric Things: On the Allure of Elemental Envelopment, Elements (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018); and, of course, this very journal.

- Dianne Chisholm, “Biophilia, Creative Involution, and the Ecological Future of Queer Desire,” in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, ed. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010), 359–360. My broader point that American nature writing privileges the earthy over the atmospheric is true not only within Whitman’s own writing (I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked/ I am mad for it to be in contact with me [1,19–20]), but it is exemplified by E.O. Wilson’s myrmecological writings and the very title of the essay collection American Earth: Environmental Writing since Thoreau. See Bill McKibben, ed., American Earth: Environmental Writing since Thoreau (New York, NY: Literary Classics of the United States, 2008).

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, xv. I’ll note that Bennett’s emphasis on the apersonal qualities of sympathy is not in tension with the robust body of literary criticism that argues for Whitman’s I as highly personal. Rather, Bennett’s formulation of sympathy illuminates the relay between the personal and apersonal, not dissolving that distinction but rather showing the interplay between them. Throughout her text, Bennett seemingly uses the terms “impersonal” and “apersonal” interchangeably; however, for the sake of consistency, I’ve opted to use apersonal, except when quoting her directly.

- In her use of atmosphere-as-metaphor, Bennett highlights qualities including diffusion, unboundedness, indeterminacy, flow, circulation, and dispersion. The only section in which Bennett does directly consider the “natural influence” of wind and air focuses on Henry David Thoreau. See Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 93–98.

- Bennett offers a helpful overview of the scholarly conversation about the (homo)erotics of Whitman’s poetry and politics (see 36–37). To her list, I would add Onno Oerlemans, “Whitman and the Erotics of Lyric,” American Literature 65, no. 4 (1993): 703–30; Byrne Fone, Masculine Landscapes: Walt Whitman and the Homoerotic Text (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992). My emphasis is somewhat different from much of this scholarship in two ways: First, I attend to a sensible, rather than literary, queerness; I’m interested in how—and by whom—this (homo)erotic disposition towards the world can be felt. Second, I privilege a queer theorization of the wind in Whitman’s poetry over the queerness of Whitman’s poetry itself.

- ’m borrowing this term from Kathleen Stewart. See Kathleen Stewart, “Atmospheric Attunement,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (2011): 445–53.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, xxii.

- Introducing Whitman by way of an earlier philosopher is, in part, inspired by one of Bennett’s essay, in which she begins with Paracelsus before turning to Whitmanian sympathy. See Jane Bennett, “Of Material Sympathies, Paracelsus, and Whitman,” in Material Ecocriticism, ed. Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 239–50.

- Titus Lucretius Carus, On the Nature of Things, trans. Martin Ferguson Smith (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2001), 3.

- Lucretius Carus, On the Nature of Things, 196.

- While agitate has negative connotations in contemporary English, the Latin agitāre means “to set in motion […] to arouse, stimulate, stir, excite, to impel, drive.” Without ignoring or dismissing the word’s most common valences today, I hope to recover the sense of agitation as an erotically exciting force. See “Agitate, v.,” in OED Online (Oxford University Press, September 2022), Oxford University Press.

- This faming of “the erotic” is consistent with Bennett’s brief section on “erotic attraction” (see 35–37), which is partly refracted through Freud. Consider, for instance, when Freud writes, “the libido of our sexual instincts would coincide with the Eros of the poets and philosophers which holds all living things together” (emphasis added). The erotic is, in this context, a kind of clinging together, the accretion of individual, not-necessarily-human selves into a larger whole. See Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, trans. James Strachey (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1961), 44.

- Bennett, “Of Material Sympathies, Paracelsus, and Whitman,” 239.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 32, 43, 62, 85.

- Throughout this paper, I use the word phenomenal in a non-technical sense to refer to the first-person experience of bodily awareness.

- This implosion of space, time, and matter comes from Karen Barad, whose model of agential realism has productive resonances with Bennett’s own thinking. In particular, Barad’s formulation of agency illuminates how sympathy can be understood as agential without assuming or necessitating intentionality. For more, see Karen Barad, “Nature’s Queer Performativity,” Qui Parle 19, no. 2 (2011): 121–58.

- Dilating, rubbing, and distilling will be discussed in this order in the paper; however, from the beginning, I want to emphasize that this order does not reflect an intrinsic prioritization. These types of sympathetic touch should be understood as existing in parallel.

- Matt Miller, Collage of Myself: Walt Whitman and the Making of Leaves of Grass (Lincoln, Baltimore, Md.: University of Nebraska Press, Project MUSE, 2010), 139–144.

- More specifically, Bennett connects Whitman’s notion of dilation to that of leaning, listing, bending, and tilting. This slanted posture is, for Whitman, mutually constitutive (To be lean'd and to lean on. [1, 176]), which will become relevant in the penultimate section of this essay. See Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 15.

- I do not mean to suggest that breath is the only means of dilating the self. Rather, I intend to highlight the repeated connection that Whitman himself makes between dilation and breath.

- Quoted in Miller, Collage of Myself, 131.

- Miller, Collage of Myself, 143.

- This willingness to open one’s body to the dilating effects of the poet’s breath is, of course, highly contingent and easily refused. For instance, in his essay on Whitman, D.H. Lawrence writes, “No, no! I don’t want all those things inside me, thank you.” D.H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (New York: Thomas Seltzer, 1923), 245.

- In a metaphorical flourish, Bennett writes that “like cream stirred into coffee, fluids and flesh comingle past the point of disaggregation” (36). I want to insist that none of the forms of sympathetic touch explored in this paper are an absolute blending. The porous seams of the self are important precisely because they are being reconstituted in response to external influences.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 32. I have removed Bennett’s original emphasis on “projection” and “dilation.”

- Much of this section — but particularly this connection between dilation, breath, and penetration — is in conversation with Emanuele Coccia’s Life of Plants in which he writes that “to breathe is to know the world, to penetrate and be penetrated by it.” See Coccia, The Life of Plants, 56.

- This is a now-familiar point within particular strands of queer scholarship. See, for instance, Tan Hoang Nguyen, A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 145.

- The transformative potential of wind has long been discussed. For example, George Didi-Huberman writes, “the wind does more than just pass over things: it transforms, metamorphoses, profoundly touches the things it passes over.” See Georges Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze: Remarks on the Air of the Quattrocento,” Journal of Visual Culture 2, no. 3 (December 2003): 275.

- This is a point that Bennett makes but does not, in my mind, draw sufficient attention to. See Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 32.

- Didi-Huberman, “The Imaginary Breeze,” 277.

- This model of relationality resists two popular threads of discourse in contemporary American politics. First, it complicates common sense ideas about polarization by questioning the delineation of an “us” versus “them.” To be clear, I’m not suggesting that all political views are equal or that antagonism isn’t a serious problem. Rather, I hope to apply pressure to rhetoric that is premised on a clear separation between self and other. Second, this model of relationality is dependent not only on the possibility of change but also its inevitability. Against political fatalism and doomsaying, I insist that the future is a site of active contestation in the present. As José Muñoz writes, queerness is felt “as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.” I suggest that queerness can also be felt as the wind’s gentle caress. See José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, Sexual Cultures (New York: University Press, 2009).

- Leo Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave?: And Other Essays (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 118. My brief reading of Bersani in this paragraph runs counter to more frequently cited conceptions of his work, especially in Homos, as foundational to the “antisocial” thesis in queer theory. I don’t intend to resolve or even engage those debates in this essay, but at minimum, I hope to elucidate one of the complexities within Bersani’s thought. For more on the antisocial thesis, see Robert L. Caserio et al., “The Antisocial Thesis in Queer Theory,” PMLA 121, no. 3 (2006): 819–28.

- Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave?, 118.

- Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave?, 33–34. Throughout this essay, I’ve tried to avoid the distinction between “human” and “non-human,” which privileges “the human” as the conceptual category from which everything else can be distinguished as other (non-human). I’ve eschewed this particular dichotomy (human/non-human) in favor of self/other and interior/exterior, both of which — although imperfect — don’t center the human quite as directly.

- I’m reminded of Deleuze and Guattari who write of “drunkenness as a triumphant irruption of the plant in us.” We might consider the intoxicating effects not only of ourselves but of nature more broadly construed. Gilles Deleuze, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 11.

- Walt Whitman, Ed Folsom, and Christopher Merrill, Song of Myself: With a Complete Commentary (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2016), 11.

- For an interesting point of comparison to Whitmanian distillation, consider the concept of decantation explored by François Jullien throughout his study of 4th century BCE Daoist philosopher Zhuanghi. For example, Jullien writes, “the man who knows how to delve within himself by purifying and decanting his breath-energy […] can recover his freely and ‘purely’ evolutive capacity and thus reconnect with the ceaseless processivity of heaven (‘keeping heaven entire in oneself,’ as Zhuangzi puts it).” See François Jullien, Vital Nourishment: Departing from Happiness (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2007), 80.

- I’m borrowing this description from Killingsworth, who reads this passage as “one of the finest instances of the Whitmanian sublime.” See M. Jimmie Killingsworth, Walt Whitman & the Earth: A Study in Ecopoetics (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2004), 22–23.

- The word transcendence is tricky in the context of a paper about Whitman. To be clear, I don’t intend on wading into the scholarly conversations about Whitman’s relationship to Transcendentalism; although, this section has unavoidable echoes of that debate. Rather, I use “transcendence” in a more limited way to convey a spatialized sense of self as “rising above/beyond” the material.

- Even though this idea of a temporally-extended reconstitution of self may — at first — sound more metaphysical than phenomenal, I want to stress that distillation remains a form of sympathetic touch. Chisholm articulates this relationship neatly (and without the religious overtones of the word “divinity”) when she writes that the “haptic is a conduit to the cosmic.” See Chisholm, “Biophilia, Creative Involution, and the Ecological Future of Queer Desire,” 274.

- Bennett uses the word “dividual” to name selves as “complex assemblages,” in distinction to “individuals,” who are conceptualized as indivisible. See Bennett, Influx and Efflux, xii–xv, 117–118.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, xx.

- For another way to understand the difficulties of and possibilities for articulating (im)material forces, impacts, and energies, see Stewart, “Atmospheric Attunement.” Stewart’s writing “tries to stick with something becoming atmospheric, to itself resonate or tweak the force of material-sensory somethings forming up” (452). Although Stewart doesn’t directly appear in Influx and Efflux, she is cited in Bennett’s 2014 essay “Of Material Sympathies, Paracelsus, and Whitman,” which prefigures many of Bennett’s arguments about Whitmanian Sympathy.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 110.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 112.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 112.

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 113–114.

- Luce Irigaray, “A Breath That Touches in Words,” in I Love to You: Sketch for a Felicity within History, trans. Alison Martin (New York: Routledge, 1996), 121–28.

- Irigaray, I Love to You, 125.

- My engagement with Irigaray’s touching upon as a form of communication is directly in conversation with the earlier section on Bersani’s notion of homoness, which was also a not-merely-linguistic communication.

- Irigaray, I Love to You, 124, original emphasis.

- Irigaray describes breath as “the safeguard of the presence of life and of its temporalization in a becoming of self non-destructive to the other” (125).

- Bennett, Influx and Efflux, 116.

- Walt Whitman, The Correspondence, ed. Edwin Haviland Miller, vol. II: 1868–1875, Collected Writings of Walt Whitman (New York: New York University Press, 1961), 151.

- Walt Whitman, The Correspondence, ed. Ted Genoways, vol. VII, The Iowa Whitman Series (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2004), 15.

Suggested Reading